Introduction

Bullying and degrading treatment are problems that most schools grapple with. There is no consensus on a definition of bullying, although it has generally been described as aggressive behaviour ‘repeated over time’, involving a ‘power imbalance’ and an ‘intent to harm’ (Jimerson, Swearer, & Espelage, 2010; Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, 2014; Olweus, 1999). This description has proved problematic although researchers have often used these three criteria. A new definition of bullying has been suggested by Volk, Dane and Marini (2014), which is: ‘aggressive, goal-directed behaviour that harms another individual within the context of a power imbalance.’ Volk et al. (2014) argue that this definition does not use the criterion of ‘intent to harm’, which is difficult to measure, and instead suggest ‘goal-directed behaviour’, which is easier to measure and predict. According to evolutionary theory, individuals bully to gain a social reputation, reproductive opportunities or resources that facilitate obtaining the first two goals (ibid.). On the other hand, when pupils are asked why bullying occurs, they say that it is because the victim is in some way different, odd or deviant (Teräsahjo & Salmivalli, 2003; Thornberg, Rosenqvist & Johansson, 2012). Another reason could be the struggle for status, power or friendship, and, in some cases, jealousy (ibid.). These different reasons are often used to justify bullying (Thornberg, 2015b).

Based on Olweus’ individual psychological perspective, the causes of bullying have usually been explained in terms of individual characteristics and behaviour (Frånberg & Wrethander, 2012). Another way of understanding bullying is to use a social-psychological (Søndergaard, 2014) and sociological perspective (Thornberg, 2015a). From this perspective, bullying exceeds the individual psychological perspective by also assigning collaborative processes between different actors, relationships and levels of importance (Espelage & De La Rue, 2012; Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002). However, bullying is understood as a social phenomenon where several factors (e.g. socio-economic, media, classroom setting) provoke the behaviour. This indicates that bullying is more complex than just one individual’s aggressive behaviour and needs to be understood in a way that takes different factors into account (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). The prevention of bullying and degrading treatment behaviour, and the creation of a safe and stable learning environment, are important parts of a school’s work.

Sweden has rigorous legislation for the prevention of discrimination and offensive behaviour (see for example the Education Act 1995:1100, 2010:800). The way that this legislation is supported by the Ministry is by means of ready-made, standardised prevention programmes that the schools can purchase. The standardised approach may, however, be insufficient, because of the schools’ different contexts (see for example Hong & Espelage, 2012; Swearer & Espelage, 2004). This is where the project presented in this article takes its starting point. The present study focuses on a locally-adapted bullying-prevention model (MBPM) in a Swedish municipality and, specifically, the practitioners’ work in implementing the programme.

Prevention strategies and programmes

Bullying is a problem that not only encompasses the perpetrator and the victim, but also affects the entire school, the peer group and the families of perpetrators and victims (Smith, Cousins & Stewart, 2005). The widespread nature of the problem has meant that schools have had to increase their efforts to prevent bullying by means of different interventions. There are several anti-bullying strategies that schools can use in order to prevent bullying. One of these strategies is a whole-school approach, which is widely recognised as an effective method because the interventions occur at different levels: the school level as a whole, the classroom level, the home level and the individual level (Evans Fraser, & Cotter, 2014).

Between 2007 and 2011 The Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE] conducted a major evaluation of the most commonly-used bullying-prevention programmes in Swedish schools. The evaluation highlighted the problem of using programmes as complete ‘packages’, largely because most schools and their particular problems are unique. The programmes mostly contained components that were found to be effective, although they were also found to include ineffective and, in some cases, counterproductive or harmful components. SNAE’s report (2011a) identified a number of approaches or programme elements that were important for bullying prevention in Swedish schools. Systematic implementation was identified as a successful approach; a whole-school approach was also found to be important in successful schools and the school climate was another aspect that helped to reduce bullying. Based on the SNAE evaluation, it is fair to assume that a bullying-prevention model needs to reflect the context in which it is to be used.

The Municipality Bullying Prevention Model

When the SNAE published its report, the schools in the municipality where the project presented in this study was conducted felt abandoned due to the SNAE’s criticism of the programmes that they had used, which meant that they needed to find new ways of working with anti-bullying. Based on the SNAE’s evaluation and findings, and in collaboration with two researchers from the local university, a Swedish municipality initiated a project that was called the Municipality Bullying Prevention Model (MBPM). The name of the municipality has been anonymised in this study. The municipality in which the project was carried out has 29 municipal and 8 privately-owned schools, all of which are governed by the same legislation. The project presented in this article includes six of these 37 schools, all located in different parts of the municipality.

MBPM encourages schools to use their own resources to work on their own problems and to come up with tailor-made solutions. The project presented here used the same pupil survey that the SNAE (2011a) used in its evaluation. The survey helped the schools to map out the different behaviours and environments, and also to measure the number of pupils exposed to degrading treatment and discrimination and the school climate. The questions touched on individual background, relations with friends, relations with teachers, class rules, experience of bullying, discrimination, own self-confidence, preventive work done in schools and the school climate (for a further explanation see the appendix and the SNAE, 2011b).

The practitioners who took part in the project were all employed in the different schools as principals, counsellors or teachers. Some of the practitioners from each school formed a safety team to take on the most serious cases of bullying. Some of the practitioners also formed specialised staff groups, i.e. groups of practitioners who were invited to special lectures about bullying and received additional email information about research and new publications from the SNAE, which they could share with their colleagues. Both teams and the other participants implemented MBPM in their particular schools. The project management group set the dates for strategy meetings for the participants and planned the content of the meetings held outside the schools. At least one person from the project management group participated in all the meetings.

The MBPM approach

MBPM makes use of decentralised reasoning (Carlgren, 1986) as an approach. Decentralisation of the school system means a clearer division between the state and the municipality, in that municipalities have a greater freedom to organise schools. This means that the employees at the schools are responsible for achieving the goals stated in the curriculum. The aim of school improvement work is to solve local problems by following the school curriculum. These actions are not supposed to be generalised to other schools, but each school uses actions that are developed at the school (ibid.). This freedom of action is what characterises decentralised reasoning.

Villegas Reimers (2003) claims that the most sustainable activities in schools draw first and foremost on their relevance to the individual school and its teachers. Legal requirements by the state are therefore only a starting point and do not, as policymakers often assume, offer solutions to the problem. It is the practitioners themselves who have to address the problems in their own contexts. No stakeholder would question that bullying prevention is important, but would perhaps point out that different schools face different issues. Schools should take into consideration the problems defined and the specific solution developed in classic school development research, which in this paper is called decentralised reasoning (Carlgren 1986).

The aim of this study is to describe and analyse how practitioners change the ways in which they work and apply decentralised reasoning to prevent bullying during the implementation of MBPM. The current project created an approach that enabled specific strategies to be adopted according to the participating schools’ specific problems and needs. MBPM helps schools to start working on their bullying problems and to change unwanted behaviour. It was important that the researchers in the project did not take over and tell the practitioners what to do, but instead allowed them to address their own problems in their own way; in other words, to implement decentralised reasoning.

Method

The action research structure of the project

This study used an action research approach to study how the practitioners changed the ways in which they worked with bullying prevention during the implementation of MBPM in the schools taking part in the project.

The project’s decentralised reasoning approach was facilitated by elements of action research, which means that practitioners applied scientific methodology to define their local problems and develop locally-embedded solutions. It was important that the project management group did not interfere in the individual schools but simply provided developmental resources. School-owned models like this aim to make schools genuinely responsible for their actions using their own resources.

The action research in this project was a participatory, democratic process that was concerned with developing practical knowledge. It was participatory, which means that the practitioners’ own experiences and actions mattered. It sought ‘…to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions for issues of pressing concern and, more generally, for the well-being of individuals and their communities’. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, p. 1).

Although action researchers examine their own practices (Kemmis, 2010), support is often provided to help them to improve these practices. Reflective practice, which is a main concept in action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2007), is defined by Johnston and Badley (1996, p. 4) as the ‘acquisition of a critical stance or attitude towards one’s own practice and that of one’s peers’. In MBPM, practitioners are constantly reminded to reflect on what they have done and why.

The project aimed to develop the practitioners’ critical and self-critical understanding of their situation (Kemmis, 2001). Critical action research has an emancipatory aspect, which means that it not only leads to new knowledge but also to new skills to create knowledge based on a critical and analytical approach (Carr & Kemmis, 1986).

The design of the project is what Martin (2001) calls a large-group intervention. The project management group defined the problem at a central level (i.e. in relation to government policy) and the practitioners defined the problem at school level. Consequently, the project management group handed the policy documents to the practitioners before the meetings and the practitioners used them in their discussions and work. This enabled the practitioners to understand what the project management group regarded as necessary in relation to policy obligations and the most recent research on bullying prevention.

The action research process applied in the project was based on cycles of action and reflection (Kemmis & Wilkinson, 1998). According to Kemmis and McTaggart (2007), this process can be more or less open and the cycles may overlap. This was the case in the project, which consisted of the preventive work that the practitioners had (or had not) been doing up to that point. Ideas were shared in the project management group and then in the practitioner group, which in turn gave rise to more reflections on practice and practical approaches.

Data collection

The number of practitioners participating in this study was between 10 and 19 per school. The data consisted of field notes taken by the researcher that were collected during the first year of the implementation of MBPM, both during strategy meetings and on visits made by the researcher to the schools. During the strategy meetings and school visits, the researcher had informal discussions with the practitioners about their ongoing work and strategies, based on their experiences from the strategy meetings and the pupil survey. Another data source was a survey that the practitioners responded to at the end of the project year. The data from that survey was both qualitative and quantitative and related to what the practitioners thought about the use of MBPM. The schools’ own quality reports provided further data.

The MBPM process

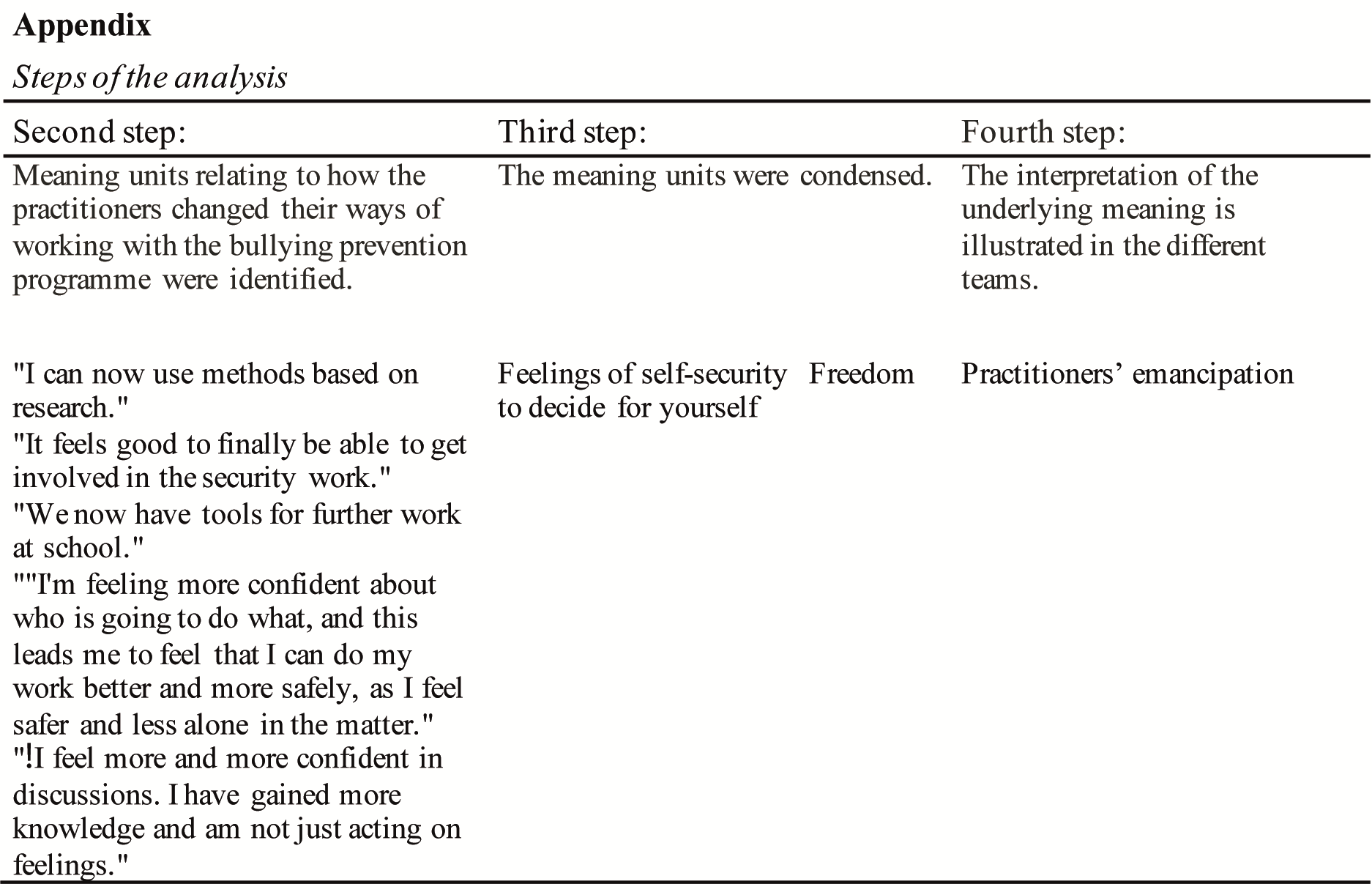

The project was completed during a school year that began in August and ended in June. The project followed cycles of action and reflection. The action research process that was used and developed is presented in Table 1.

The strategy meetings were significant nodal points for the different action cycles. The project management group decided on four meetings in the first term. In the second term, the idea was that practitioners from the schools would be offered coaching by the local team responsible for crime prevention, before the second pupil follow-up survey was carried out.

During the meetings, practitioners from the participating schools were encouraged to work with colleagues at the same school level.1 This enabled them to discuss their own contexts and cultural conditions. The meetings were followed by a survey evaluation that was carried out and analysed by the project management group and used to plan the next meeting. These surveys were only used to plan the next meeting and do not provide data in this study.

Moreover, the process was supported by relevant material provided by the project management group. At the first meeting (cycle 1), all the practitioners received a folder containing texts offering different perspectives on bullying-prevention work, discrimination, violence, aggression and offensive behaviour. The folder included policy documents, such as chapters on equality and anti-discrimination plans, value systems, safe and good learning environments, the Education Act (2010:800), the Equality Act (2008:567), the compulsory school curriculum (Lgr 11) (SNAE, 2011c) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Unicef 1990). Information about how to discover, prevent and remedy antisocial behaviour based on SNAE publications (2011a) was also included. The material served as a trigger to generate further elaboration and discussion for the meetings that followed (cycles 2 and 3).

Finally, and most importantly, the practitioners received the questionnaire tool described earlier (cycles 4 and 7) and were shown how to use it. In the following meetings, the practitioners had the opportunity to work with their colleagues and receive coaching from the management group (cycles 5, 6 and 8).

Analysis strategy

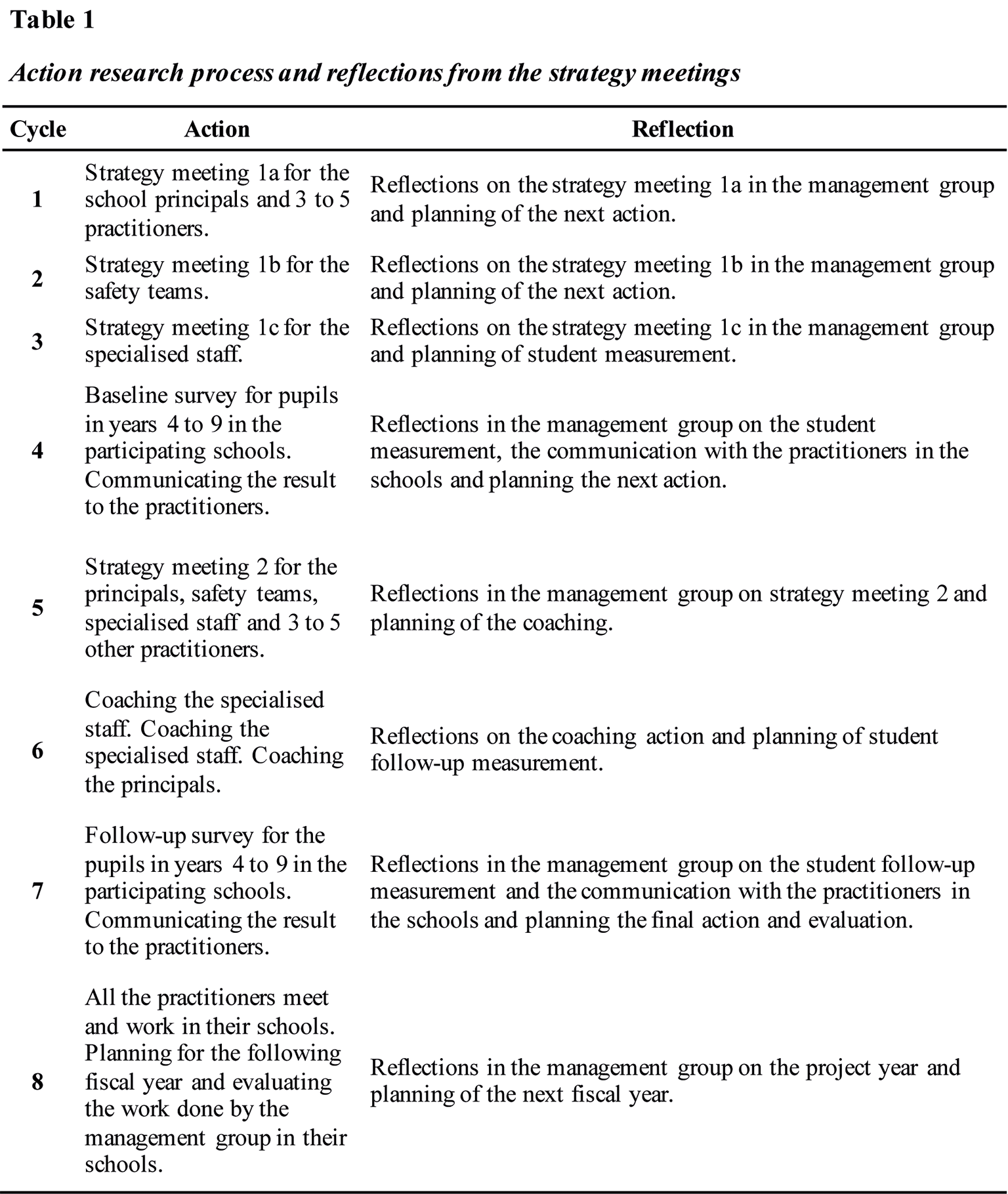

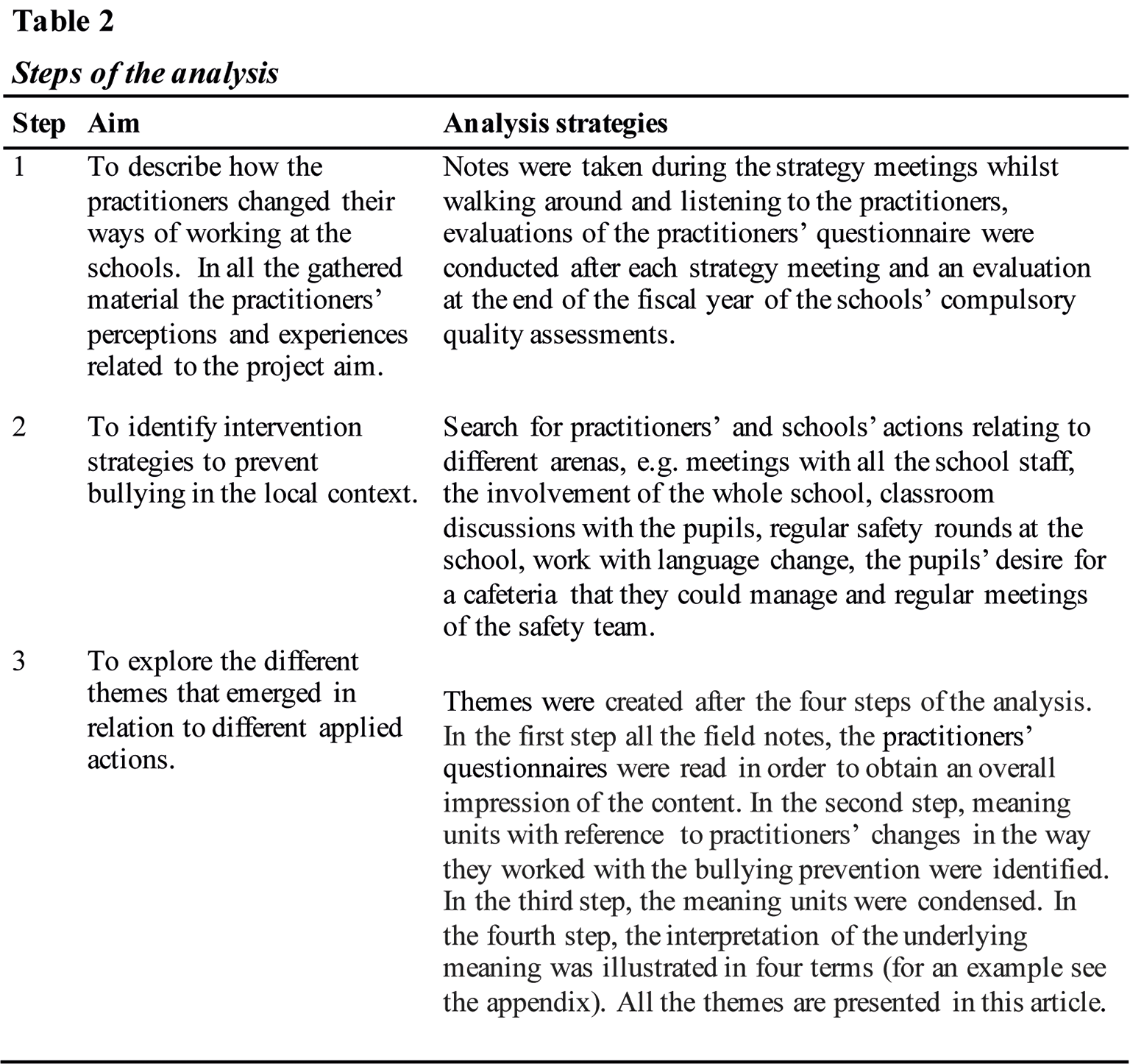

The findings were generated by content analysis strategies (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Sandelowski, 2000). Themes then emerged from analysis of the collected data. The analysis strategy was formulated during the first year of the implementation of MBPM. The analysis steps that were created and used are presented in Table 2.

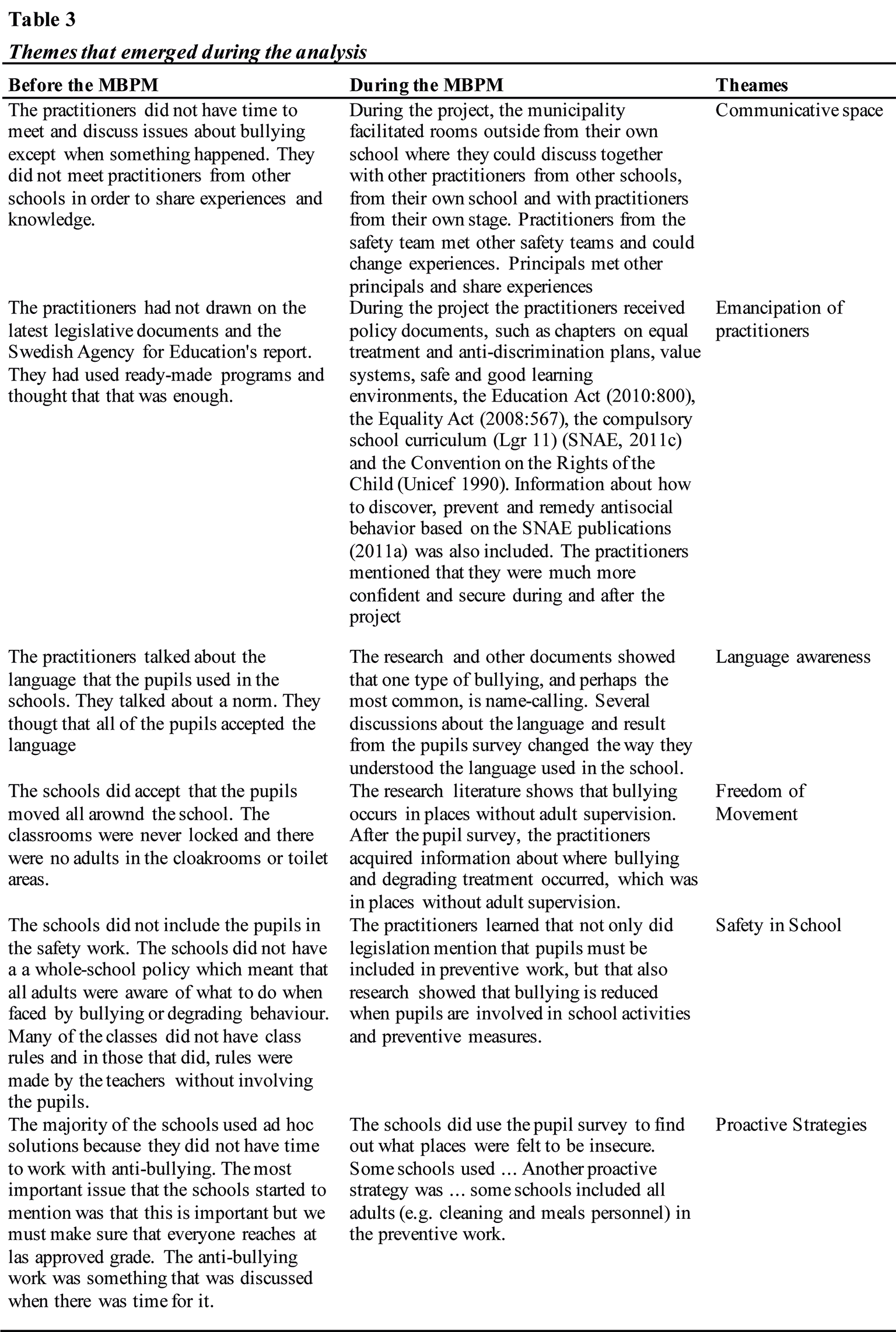

Six themes emerged during the analysis of the data which illustrated how the practitioners worked. These themes were: (i) communicative space, (ii) the emancipation of practitioners, (iii) language awareness, (iv) freedom of movement, (v) safety in school and (vi) proactive strategies. These themes and how they emerged are presented in Table 3.

Findings

The actions that were taken basically indicated that all the practitioners in the individual schools were involved at some point, and related to the significance of coping with bullying as a whole-school approach. All the quotations included in this article come from the practitioners but do not relate to a particular staff member or school.

The schools began to introduce the various actions in several places and at different levels during implementation of MBPM (school level, classroom level and individual level). Here, the six themes that emerged in the analysis are presented with quotations from the practitioners.

Communicative space

In the strategy meetings, the practitioners were able to discuss MBPM and begin the school’s bullying-prevention work. One of the practitioners said:

It’s good to discuss and exchange experiences with other schools. Good to get a boost in this work. The format is good and the tips, thoughts etc. will be taken into account when we meet the practitioners from the different schools. Good to have input from other schools.

They also talked about the importance of support from the principal in bullying-prevention work and said that they could now plan and allocate time to prioritise anti-bullying work. They pointed out that earlier work at the school had not been successful and that other aspects (e.g. grades, national tests) had been prioritised. ‘The principal must be on board, otherwise other work will be prioritised, such as knowledge requirements’. (practitioner). Reflection and discussion thus became important and were made possible due to the communicative space that had been created. One major limitation in the work at the schools was that the principals did not support the staff in the way the latter felt was necessary. They became aware that the school leader’s involvement and planning of efforts to prevent bullying were crucial for what needed to be done, and that without this support the work would not be effective, or could even fail. Even the principals understood the importance of being involved in the work and set aside time at the beginning of the term to work on bullying issues. One practitioner emphasised that ‘The staff must feel strongly supported’.

Another form of support that the practitioners considered important was the support they received from the management group in the form of lectures, literature and a communicative space. One practitioner formulated it thus, ‘Good support for the continued work at the school’.

According to Kemmis (2001), the formation of a communicative space is central in any action research project. Wicks and Reason (2009) explain that a communicative space is embodied in networks of people where the problems that the participants have are openly discussed. In a communicative space, the interaction of the participants and their different views and experiences are taken into account. Finally, what should be done in order to deal with the problems is agreed on democratically in the form of consensus. During the meetings, the practitioners created a communicative space in which they could talk and reflect on their various practices (see, for example, Elliott, 1991). The practitioners thus had an arena in which they could meet, exchange and share their experiences (Kemmis, 2012) and effectively coordinate their actions and orientations. Kemmis calls this communicative action.

Emancipation of practitioners

At the first meeting with the practitioners, it was pointed out that the project aimed to achieve the emancipation of schools and practitioners, especially when it came to choosing and using methods to define their problems and develop local solutions. It was also explained that the management group would provide support to the practitioners, but not control the work of the individual schools.

Before MBPM was introduced, the schools had worked in accordance with what the principal or an anti-bullying group had planned. Many schools did not have any systematic anti-bullying work in place. Instead, the efforts were somewhat ad hoc. Some of the schools used ready-made programmes that they had purchased.

The practitioners, and especially the safety team, wanted long-term solutions and training in the methods used in the project, although this was not within the project’s framework. The starting point of the project was that there were no long-term solutions or method training, but that each school was unique and had its own unique context. Therefore, the project was based on a decentralised reasoning that aimed at emancipation for the schools. MBPM was not meant to be perceived as ‘top down’, despite the fact that work to prevent degrading treatment was a legal requirement. The practitioners seemed to take this framework into account and started to change the way they related to each other and to the schools anti-bullying work. One practitioner said that ‘There are good opportunities to discuss the school’s different cases.’

The management group set the framework for the content during the strategy meetings but could not influence the internal work of the schools. The schools designed the content according to their needs and, in so doing, became more confident in their preventive work, expressed by practitioners thus, ‘We work in a different way in school than before, due to research’ and ‘I am more secure in my role’.

Within action research, the aim is for practitioners to reach a better understanding, as well as practical improvement, development and innovation of their practices (Zuber-Skerritt, 2003). The involvement of practitioners is important, as it is their practices that are developed (Rönnerman, 2012a).

Language awareness

Several actions changed during implementation of MBPM. One of them was name-calling, which is a well-known phenomenon among school children.

The language used in the schools turned out to be more important than the practitioners had realised. In fact, the language norms of the practitioners and the pupils did not match. In one of the schools, the language used by some of the pupils was regarded as insulting. The teachers said that they realised that such language was normal for school children but did not like it. Swear words and name-calling were prevalent amongst both sexes. The survey informed the practitioners about the pupils’ perceptions of the language they used between themselves and, rather surprisingly, both the pupils and the practitioners agreed that some of the language was unwarranted.

The schools involved in the study changed their language policies and the staff intensified their school rounds, especially in the cloakrooms, where pupils had reported the occurrence of offensive behaviour. One school reported that ‘We have discussed the pupils’ language and have had discussions about it in mentor groups’. (practitioner). Another school organised special activities for the pupils:

Pupils are encouraged not to verbally offend each other. After each break, all pupils put a pea in a can if they have not said anything offensive to anyone. When a certain number of peas are in the can, the class is rewarded. (practitioner).

In this way, the schools began to pay attention to language and it became a learning process for practitioners, especially as there was a discrepancy between the language usage that the practitioners thought was the norm in the school, and the kind of language pupils were accustomed to.

Since verbal bullying, such as name-calling, is the most common form of school bullying both for boys and girls (Garandeau, Poskiparta & Salmivalli, 2014; Waseem & Nickerson, 2017), it cannot be ignored. Name-calling is when one child refers to another with an unkind label, which can be mild, moderate or severe (Sahranc, 2015). According to Birkett and Espelag (2015), homophobic name-calling is one of the most common forms of victimisation in school and leads to an increased level of suicides.

Freedom of movement

Another change was the notion that bullying could occur anywhere in school, including the classroom: ‘Now we always try to make sure that there are adults in the classrooms’. (practitioner).

In one of the schools, the pupil survey revealed that the main problem was bullying in the classroom, which came as a surprise to the teachers involved, as no one had suspected it. The principal had allowed the pupils to use the classrooms during the breaks but, due to the findings of the survey, he decided to lock all the classrooms when classes were not in session. In the follow-up survey, it became clear that the amount of bullying and abuse had decreased and that this kind of behaviour no longer took place in the classroom. In this particular school, the problem occurred during the breaks, when the teachers were in the staff room. Even though the problem of bullying still existed, the teachers were now much more aware of the problem.

Research indicates that bullying in the classroom is commonplace. Atlas and Pepler’s (1998) research indicates that bullying episodes in the classroom should be identified as 53% verbal aggression, 30% physical aggression and 17% as a combination of both. In the study, the teachers were unaware of the bullying and peers were reluctant to intervene. Šimegovás’ (2009) research also reveals that the most common place for bullying is in the classroom.

Safety in school

The school environment was also given attention during implementation of the project. Pupils who participate also have a more positive view of school, which improves the school climate. The participation of pupils in the making of school policy against discrimination and degrading treatment is also legislated for in Sweden (e.g. SFS 2006:1083), and here the SNAE points to a positive outcome in the reduction of school bullying. However, the pupils participating in the project had not been included in the schools’ anti-bullying work. Instead, the schools carried out actions that the principal and practitioners thought were good for the school and the pupils. The schools thus took actions that they thought would benefit the pupils, without finding out what the pupils thought about them.

MBPM advocates that pupils should participate in a school’s preventive and remedy work. During the use of MBPM, the pupils were invited to participate. Here is one quote from the practitioners about pupil participation in the schools’ preventive work:

We have discussions in class about safety in school. (practitioner).

One school set up a school cafeteria as a strategy for reducing bullying. The school cafeteria created a good atmosphere and the adults in the school supported the pupils in this endeavour. Some of the practitioners pointed out the importance of making an effort where it was most needed:

We increased the number of adults outside during the break and ensured that adults were in the cloakrooms after lunch so that the children felt safe. (practitioner).

School safety is important to prevent bullying. When pupils are involved in bullying, their perceptions of the school’s psychosocial environment are often negative (Meyer-Adams & Conner, 2008; Olweus, 1993). According to SNAE (2011a), pupils should participate more at school. In successful schools, pupils participate and these schools have developed relationship-enhancing measures. Earlier research also indicates that bullying mostly occurs in school cafeterias (Parault, Davis & Pellegrini, 2007; Selekman & Vessey, 2004), on the journey to and from school, on the bus, in school corridors, in locker areas, in the gym locker rooms and in the playground (ibid.).

Proactive strategies

Before the project began, the schools carried out several surveys that addressed different areas, although none addressed all the areas that could be linked to bullying (e.g. degrading treatment, bullying, discrimination and school climate). In contrast, MBPM initiated a pupil survey that addressed all these areas. At one school, it became apparent that the pupils did not know anything about the safety team or what to do about bullying. One proactive measure was therefore the development of a safety team. Even though all the participating schools had some kind of safety team in place before implementation, developing these teams became a major priority among the practitioners. During implementation, the safety teams were encouraged to discuss different issues and to draw up plans to counteract bullying.

School safety issues and the safety team have been given a more important role in the school and we can see the benefits of including these issues in everyday life in a more natural way. (practitioner).

In many cases, this learning process developed slowly during the project year and was not something that happened immediately. A year was required for the project, due to the amount of literature that the practitioners had to read and also for participation in the communicative space that was created in that year.

Clear routines are needed for the safety team. We have become better at seeing what the contact teacher’s task is and what the safety team’s tasks are. We have also been better at giving feedback to perpetrators who have improved. (practitioner).

Another proactive measure was the whole-school approach, which the schools started to work with, using the survey as a mapping method.

All the staff, including the cleaning and school meals personnel, have participated in a half-day information seminar. (practitioner).

One of the effects of the implementation was that the schools started to work more systematically with bullying. However, the schools did not all work in the same way with the same issues. This depended on each school’s own context.

Thompson and Smith (2011) recommend the use of proactive strategies to deal with episodes of bullying and to prevent it from happening. Some of the strategies that are recommended are direct sanctions, restorative approaches, support group method and school tribunals. One proactive strategy is the whole-school approach, which has been successful in several anti-bullying programmes and means that all the adults working in a school need to know what to do and who they can contact if something happens (Evans, et al. 2014; Farrington & Ttofi 2009; Olweus 2004).

Discussion

The action research project gave a better understanding of the importance of listening to the practitioners’ voices, as they they provide information about how and why different actions have positive outcomes.

The schools have to handle the different problems that either emerge in the survey or are expressed by the pupils. At the beginning of the project, the practitioners were cautious and suspicious, especially of the researcher. They wanted a hands-on programme that told them what to do, step by step. One practitioner said, ‘Researchers come into school, do their research, discover problems and then leave the school to deal with them’. (practitioner). However, at the end of the project year, the practitioners were much more confident and trusted their own knowledge.

The project created different communicative spaces for the practitioners (Kemmis & McTaggart 2005), for example, in the larger group made up of all the practitioners, in the school groups where problems were discussed from a whole-school perspective, and in the small groups where problems and possible solutions were discussed. In these communicative spaces, teachers were able to reflect on their practices using the material that was provided. At the end of the project, the teachers could relate their interactions to what they knew and how they acted (Dall’Alba & Sandberg 2010). Through the group work, they moved from seeing some of their own issues as unique to seeing them as young people’s social behaviour in general. In other words, they were able to see their problems from another perspective.

The practitioners thought that discussing and meeting other practitioners was important in their learning process. Sherer and Nickerson (2010, p. 218) suggest two approaches for involving school staff in preventive work: ‘providing staff training and increasing adult supervision’. As early as 1947, Lewin wrote about training key people who could then train others in the target group.

The schools’ proactive work gained momentum during implementation of MBPM. Clarke and Kiselica (1997) suggest a systematic, whole-school intervention programme consisting of several components. The philosophical component means that no adult in the school will tolerate bullying. The schools started to work with the whole-school approach. In one of the schools, the cleaning and school canteen personnel also participated in information seminars. Clarke and Kiselica (1997) highlight the importance of having policies that prohibit bullying and emphasise that adults must set a good example. These policies must also consider the consequences of bullying (Smith, Schneider, Smith and Ananiadou, 2004) and should be upheld by everyone in the school (Smith, et al., 2005). During strategy meetings, the practitioners were able to engage in the schools’ preventive work. Clarke and Kiselica also point to the importance of having an educational component to educate all the stakeholders about bullying behaviour. This is something that emerged during the strategy meetings in the large group and also in the practitioners’ communicative space. Clarke and Kiselica maintain that educational components should include everyone in the school, and that all forms of bullying should be reported.

According to Furlong, Felix, Sharkey and Larson (2005), a safe school has to be purposefully planned and organised and this begins with the formation of a safety team that is responsible for developing a prevention plan. The safety team is not expected to implement the plan alone, but to include other stakeholders, such as administrators, faculty members, staff members, parents, pupils and members of the local community, in the work. This is because bullying stems from complex interactions between individuals and the contexts in which they function, both proximal (i.e. family, peers, school climate) and distal (i.e. societal, cultural influences) (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and this is why the plan should be based on a whole-school approach (Furlong et al. 2005).

Supported decentralised reasoning

The focus in this action research is on sustainability and quality, in terms of the quality of the outcome. If the findings are seen from a critical perspective, it is important that the intervention project is not limited by the need to fit it into a limited time frame (Mockler, 2014). Rönnerman (2012b) uses the terms depth, length, breadth and relationships to show how an action research project can be sustainable. She believes that depth is crucial for sustainability. In the project reported on in this article, depth means that the practitioners deepen their knowledge of bullying-prevention work (e.g. research literature, Swedish school policy, communicative spaces). Since the project lasted for one year, a relationship could be established between the management group and the practitioners.

As practitioners talk to colleagues from other schools, breadth emerges. Based on Rönnerman (2012b), the project can be seen as a sustainable development for the schools’ prevention, promotion, discovery and action work. Action research was a useful tool for including practitioners in the schools’ preventive work and for achieving sustainability.

The process of action, re-action and pro-action should continue, albeit with some adjustment to fit the various situations. The municipality could help schools to monitor and evaluate the processes and outcomes, so that the schools can own the preventive work and make use of the cycles that have been used in the project. In this study, the possibility of using outside-school premises was crucial for working in a way that can be termed decentralised reasoning.

At this point it is appropriate to adjust the term decentralised reasoning (Carlgren 1986) to supported decentralised reasoning, because this could lead to local solutions that are tested in an evidence-based way. That means that the schools use solutions that are adjusted to the school’s own context and that they know are successful. Although this might turn out to be cheaper, because they do not need to buy ready-made programmes, it would take more time. Moreover, the schools may not be able to handle the data collection or meetings with colleagues from other schools and may even need new research input.

The examples presented in this article indicate that the anti-bullying strategies developed are often on a minor scale, which could reflect the realities of the schools. The examples also indicate that the probability of development increases when an individual school’s horizon of possibilities is drawn on and the whole school is considered in relation to particular prevention strategies. Here, minor strategies may lead to major change. The different activities employed by the schools are often familiar practices in schools with good social climates (Zullig, Koopman, Patton, & Ubbes, 2010), such as being aware of language use, having control over the classroom, even during the breaks, establishing social meeting places such as school cafeterias, or having safety teams that can mediate in arguments between pupils.

Even by implementing the whole-school approach, only slow developments for the better should be expected (Lee, Kim, & Kim, 2013). At the same time, bullying is not an easy matter to deal with. Even though bullying has been explained as an individualistic approach, it has expanded to be seen as a social and dynamic process (second paradigm on bullying) (Thornberg, 2015a). This means that literature, and specially that which practitioners read, needs to be developed, broadened and translated into the language that is used in the schools, so that they understand that is not only about individual explanations.

Limitation

Although the project was developed and maintained by the project management group, MBPM proved to be vulnerable, in that only one person from the management group worked full-time on the project. What would have happened if this person had stopped doing that? The schools depended on a person who was an enthusiast, but there was no one else in place who could do the job. Here, the group management, and especially the municipality, need to think about having a replacement or an additional number of people who can support the schools in their anti-bullying work. In other words, the support decentralised reasoning needs to expand and develop.

As the project was a collaboration with the municipality, the practitioners were guaranteed support from the municipality. Everyone participated voluntarily, which could be why the outcomes were positive for the practitioners and for MBPM. It might have been different if the schools had been forced to use MBPM. Another reason may be that the head of the compulsory school division was in the project management group. Also, the article only presents what the practitioners discussed and said, and the findings therefore indicate their perceptions and what they said was done in the schools. The researcher never visited the schools to see what was actually being done, which may have resulted in perceptions that were different from those of others (e.g. pupils, other practitioners and adults in the schools). Even if the article does not show whether the number of pupils subjected to bullying has decreased, MBPM at least initiated collaboration between the practitioners, schools and municipality.

As the analysis was conducted by the author of this article, the themes may have been different if other researchers had carried out the analysis. The researcher’s own knowledge and the theory used in the project could have affected the analysis. Morrow (2005) writes that all research is subject to researcher bias and is influenced by the research paradigm. In this research, this paradigm is action research, which is subjective and uses particular theories and concepts. This can be seen in the themes created in this project, even though it was the data that constituted the themes.

The project may be used in other municipalities but the outcome may be different because the project management group will be different without one person who is an enthusiast. When the project started, the schools wanted help, they were voluntary - this might be different in other municipalities. Support for decentralised reasoning should be transferable to other municipalities though. A next step in MBPM would be to analyse the pupil survey in order to see whether the model has had any real effect on bullying.

References

- Carlgren, I. (1986). Lokalt Utvecklingsarbete [Local Development Work]. Göteborg: Göteborg Universitet.

- Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge and Action Research. London: Falmer Press.

- Clarke, E. A., & Kiselica, M. S. (1997). A systematic counseling approach to the problem of bullying. Elementary School Guidance & Counseling, 31(4): 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78

- Dall’Alba, G., & Sandberg, J. (2010). Learning through and about practice: A lifeworld perspective. In Billett S. (Ed.), Learning through Practice (pp. 104–119). Netherlands: Springer.

- Department of Culture. SFS 2008:567. Diskrimineringslag [The Equality Act]. Stockholm: Kulturdepartementet [Department of Culture].

- Department of Education. SFS 2006:1083. Förordning om barns och elevers deltagande i arbetet med planer mot diskriminering och kränkande behandling [Ordinance on Children’s and Pupils’ Participation in the Plans against Discrimination and Degrading Treatment]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet [Department of Education].

- Department of Education. SFS 1985:1100. Skollag [The Education Act]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet [Department of Education].

- Espelage, D. L., & De La Rue, L. (2012). School bullying: its nature and ecology. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 24(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh.2012.002

- Evans, C. B., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 532–544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004

- Farrington, D., & Ttofi, M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 5(6). https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2009.6.

- Furlong, M. J., Felix, E. D., Sharkey, J. D., & Larson, J. (2005). Preventing school violence: A plan for safe and engaging schools. Principal Leadership (High School Ed.), 6(1), 11–15.

- Frånberg, G., & Wrethander, M. (2012). The rise and fall of a social problem: Critical reflections on educational policy and research issues. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 10(2), 345–362.

- Garandeau, C. F., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). Tackling acute cases of school bullying in the KiVa anti-bullying program: A comparison of two approaches. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(6), 981–991.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9861-1

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jimerson, S. R., Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Johnston, R, & Badley, G. (1996). The competent reflective practitioner, Innovation and Learning in Education. The International Journal for the Reflective Practitioner, 2(1), pp. 4–10.

- Kemmis, S. (2010). What is to be done? The place of action research. Educational Action Research, 18(4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2010.524745

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2005). Communicative action and the public sphere. Denzin, NK & Lincoln, YS (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3, 559–603. London: SAGE Publications.

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2007). Participatory Action Research. Communicative Action and the Public Sphere. In. Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2007). Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry, Third Edition. London: SAGE Publications.

- Kemmis, S. (2001). Exploring the Relevance of Critical Theory for Action Research: Emancipatory Action Research in the Footsteps of Jürgen Habermas. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry & Practice (pp. 91–102). London: SAGE Publications.

- Kemmis, S., & Wilkinson, M. (1998). Participatory action research and the study of practice. In B. Atweh, S. Kemmis, & P. Weeks (1998), Action Research in Practice. London: Routledge.

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0

- Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in Group Dynamics II. Channels of Group Life; Social Planning and Action Research. Human Relations, 1(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674700100201

- Lee, S., Kim, C., & Kim, D. H. (2013). A meta-analysis of the effect of school-based anti-bullying programs. Journal of Child Health Care, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493513503581

- Martin, A. W. (2001). Large-group Processes as Action Research. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry & Practice (pp. 166–175). London: SAGE Publications.

- Meyer-Adams, N., & Conner, B. T. (2008). School violence: Bullying behaviors and the psychosocial school environment in middle schools. Children & Schools, 30(4), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/30.4.211

- Mockler, N. (2014). When ‘research ethics’ become ‘everyday ethics’: the intersection of inquiry and practice in practitioner research. Educational Action Research, 22(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2013.856771

- Olweus, D. (2004). The Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme: Design and implementation issues and a new national initiative in Norway. In P. K. Smith, D. Pepler & K. Rigby (Eds.), Bullying in Schools: How Successful can Interventions be? (13–36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Olweus, D. (1999). Norway. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The Nature of School Bullying: A Cross-National Perspective (pp. 7–27). London: Routledge.

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bully/victim problems among schoolchildren: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In D. J. Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.) (1991). The Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression (411–448). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

- Parault, S. J., Davis, H. A., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2007). The social contexts of bullying and victimization. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(2), 145–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431606294831

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. London: SAGE Publications.

- Rönnerman, K. (Ed.). (2012a). Aktionsforskning i Praktiken – Förskola och Skola på Vetenskaplig Grund. [Action Research in Practice –a Scientific Base for Pre and Primary School on]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Rönneman, K. (2012b). Sustainability. In S. Groundwater-Smith, J. Michell, N. Mockler, P. Ponte & K. Rönneman (Ed.), Facilitating Practitioner Research: Developing Transformative Partnership. (pp. 73–90). London: Routledge.

- Sahranc, U. (2015). Coping with Teasing and Name-Calling Scale For Children. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 12(1).

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Selekman, J., & Vessey, J. A. (2004). Bullying: It isn’t what it used to be. Paediatric Nursing, 30(3), 246.

- Sherer, Y. C., & Nickerson, A. B. (2010). Anti-Bullying Practices in American Schools: Perspective of School Psychologist. Psychology in the Schools, 47(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20466

- Šimegová, M. A. (2009). Bullying and bully in school setting as the actual problem of education in Slovak Republic. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 15.

- Smith, J. D., Cousins, J. B., & Stewart, R. (2005). Antibullying interventions in schools: Ingredients of effective programs. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 739–762. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126453

- Smith, J. D., Schneider, B. H., Smith, P. K., & Ananiadou, K. (2004). The effectiveness of whole-school antibullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review, 33(4), 547–560.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011a). Utvärdering av metoder mot mobbning [Evaluation of Anti-Bullying Methods]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011b). Utvärdering av metoder mot mobbning. Metodappendix och bilagor till rapport 353. [Evaluation of Anti-Bullying Methods]. Method Appendices and Supplement to the Report 353]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Swedish National Agency for Education (2011c). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet [Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Recreation Centre] 2011 (Lgr 11). Stockholm: Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education].

- Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038929

- Swearer, S.M., & Espelage, D.L. (2004). Introduction: A social-ecological Framework of Bullying Among Youth. In D. L. Espelage S. M. & Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American Schools: A Social-Ecological Perspective on Prevention and Intervention (1–12). London: Routledge.

- Søndergaard, D. M. (2014). Social exclusion anxiety: Bullying and the forces that contribute to bullying amongst children at school. School Bullying: New Theories in Context, 47–80.

- Thompson, F., & Smith, P. K. (2011). The Use and Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Strategies in Schools. Research Brief DFE-RR098.

- Thornberg, R. (2015a). The social dynamics of school bullying: The necessary dialogue between the blind men around the elephant and the possible meeting point at the social-ecological square. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy and Politics, 3(2), 161–203. https://doi.org/10.3384/confero.2001-4562.1506245

- Thornberg, R. (2015b). School bullying as a collective action: Stigma processes and identity struggling. Children & Society, 29(4), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12058

- Thornberg, R., Rosenqvist, R., & Johansson, P. (2012). Older teenagers’ explanations of bullying. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-012-9171-0

- Unicef (1990). Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- Waseem, M., & Nickerson, A. (2017). Bullying. PMID: 28722959.

- Wicks, P. G., & Reason, P. (2009). Initiating action research: Challenges and paradoxes of opening communicative space. Action Research 7(3), 243–63.

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2003). Emancipatory action research for organisational change and management development. In New Directions in Action Research (pp. 78–97). London: Routledge.

- Zullig, K. J., Koopman, T. M., Patton, J. M., & Ubbes, V. A. (2010). School climate: Historical review, instrument development, and school assessment. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282909344205

Noter

- 1 In Sweden, children attend primary school from six years of age, from Year 1 to Year 3, with a voluntary school year prior to the first year. Middle school is from Year 4 to Year 6 and secondary school from Year 7 to Year 9.