Introduction

This article is the result of an international collaboration between two academics who both work closely with Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) at local schools. Our aim with this article is twofold. Firstly, we seek to apply an analytical model for the purpose of enhancing collegial learning by challenging assumptions about purposes, tools and practices. In particular, we apply the analytical model to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences and missing links in such conversations. Secondly, our intention is to explore how this model may provide a lens for researchers working together as critical friends. In this context, we hope that the model may highlight silences and ‘why’ considerations when one researcher (A) challenges their critical friend’s (researcher B) assumptions and interpretations about B’s study context and vice versa.

In regard to the latter, our research collaboration was initially prompted three years ago when one author (the Australian) contacted the other (Swedish) author, after reading one of the latter’s articles about their research as a critical friend to a PLC in Sweden. The Australian author had come across this publication while in the process of reflecting on and researching their own practice as a critical friend to a PLC at a school in regional Australia. This initial, incidental common point of interest has grown into an intercontinental collegial research collaboration, framed around our reflections about our work with PLCs in our respective contexts.

Drawing on seminal reviews of research into PLCs (for example, Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008), we define the term ‘PLC’ as an organisational structure with a core purpose of developing teachers’ professional knowledge and enhancing student learning through critical reflection and collegial conversations. Such collegial conversations generally require an evidence base, in the form of students’ work samples, instructional plans or teaching materials, upon which discussion between teachers is centered (Little & Curry, 2009). However, data-based conversations do not just involve adding data to the conversations—they require the adoption of a way of thinking and of challenging ideas in pursuit of new knowledge (Earl & Timperley, 2009). In turn, challenging the status quo and adopting new ways of thinking entail data-informed changes to practice. Previous research suggests that sustainable change does not occur within a PLC unless the participants feel empowered as professionals, understand the aim and underpinning principles of change initiatives and explore ways of implementing new ideas and learning, integrating them into their existing practices, structures and processes (Butler et al., 2011; Jacobsen & Buch, 2016). Initiatives to develop professional knowledge require that opportunities for reflection and the exchange of ideas are created, by which collegial conversations about teaching and learning become merged with deep collaboration involving evidence and inquiry (Butler et al., 2011; Earl & Timperley, 2009; Samuelsson, 2018).

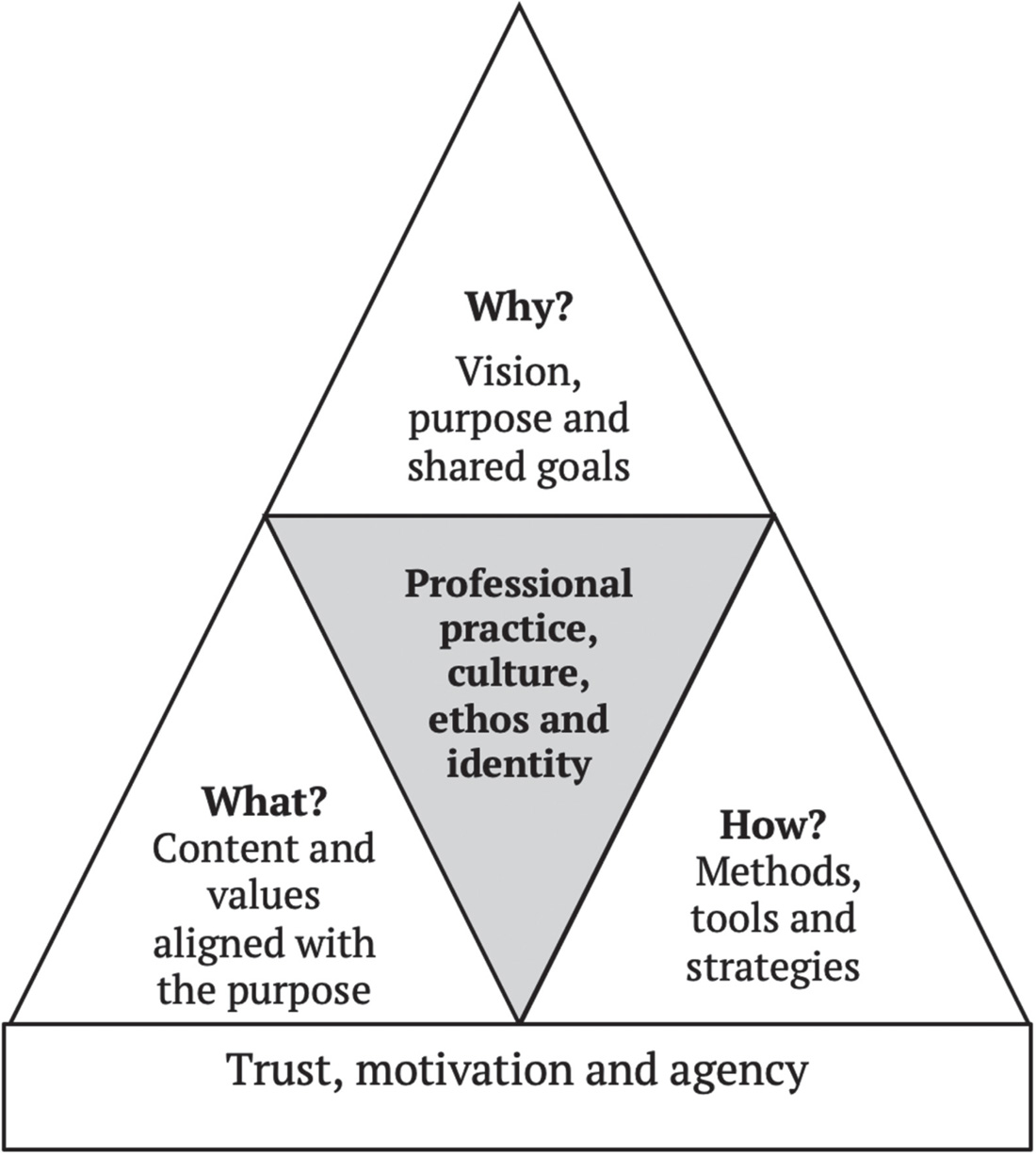

The aim of this article is to apply an analytical model to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences or missing links in collegial learning conversations. The research was guided by three core considerations: What? Why? How? Of these, ‘what’ constituted content (aligned with the purpose); ‘why’ articulated the PLC’s purpose and its shared goals; and ‘how’ referred to the repertoire of systematic methods, tools and strategies which the PLC applied to achieve its purposes.

PLC identity

Before outlining the focus of this article—applying an analytical model to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences or missing links for the purposes of enhancing learning and challenging assumptions about purposes, tools and practices within a PLC—it would be appropriate to clarify how we conceptualize key elements of a PLC and our roles as researchers within such. As stated above, the core purpose of a PLC is to develop teachers’ professional knowledge and enhance student learning through critical reflection and collegial conversations. However, the nature of the critical reflections and conversations within a PLC is characterised and framed by the shared professional identity of the group. The professional identity, in turn, is constituted by common reference points.

The literature includes several helpful conceptualizations of common reference points on which a community identity is built. For example, Banks (1998) presents a cross-cultural framework to understand community which includes values, perspectives, behaviours, beliefs and knowledge as its defining points. A recent adaption of Banks’ framework incorporates features of effective learning communities (Coates, 2017; Woods & Macfarlane, 2017), in which a PLC’s common reference points relate to shared vision, values, culture and ethos (Fletcher, 2019). The term ‘vision’ refers to those common ideals and goals the PLC aspires to achieve. ‘Values’ refers to the PLC standards of behaviour and beliefs about what is important. ‘Culture and ethos’ is to be understood as the spirit of the PLC, the climate which is manifested in its shared customs, rituals, symbols, stories and language (Woods & Macfarlane, 2017).

Svedberg (2016) offers a different way of looking at a PLC by presenting professional identity as a concept that is framed by three considerations—why, what and how—which in turn are founded on trust, motivation and significance. In Svedberg’s (2016) framework, ‘why’ articulates the group’s purpose and its shared goals; and ‘what’ refers to focal points that align with the group’s purpose, which therefore are prioritised and deemed to be essential. The third consideration, ‘how’, refers to the repertoire of systematic methods and strategies which the group applies as a collegial body to achieve its purposes. The ‘how’ consideration also takes into account what strategies the group employs to gauge progress and determine whether the methods used are effective for achieving the group’s goals.

When applied to the context of this article (Figure 1), in which a PLC is an organisational structure, ‘what’ constitutes content that aligns with the PLC’s purpose, ‘why’ relates to the strategic goal of the PLC, and ‘how’ refers to the repertoire of systematic methods, tools and strategies which the PLC applies to achieve its purposes. These concepts are underpinned by a foundation of trust, motivation and agency. As noted by PytlikZillig and Kimbrough (2016), the literature has variously defined trust is a behavioural, cognitive or affective construct which may be manifested through beliefs, attitudes, intentions and behaviours. Drawing on previous distinctions and definitions of trust (Castaldo et al., 2010; Li, 2007; Rousseau et al., 1998, cited in PytlikZillig and Kimbrough, 2016), we conceptualize trust within a PLC context as a relational, interdependent relationship between a trustor who relies upon a trustee in a context which includes uncertainty, vulnerability and/or risk. We see trust as an affective and cognitive outcome, which is built through an emotional process that involves action and expectations. Trust is widely seen as an essential factor for learning (Baskerville & Goldblatt, 2009; Swaffield, 2008; Zimmerman Nilsson et al., 2018). While trust is largely dependent on personal relationships, it may be developed through the sharing of knowledge about learning, methods and analytical tools which can be used to facilitate improvements in teaching practice. The second foundation component on which the pyramid is based is motivation. In this article, motivation is understood as a concept covering intentions and factors that promote the way people understand the relationship between the particular behaviour they engage in and the particular outcomes they expect to achieve as a result (Deci et al., 1991; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). The third element that underpins group professional practice is agency, which refers to the idea that people intentionally exert influence over their functioning and the course of events that results from their actions (Bandura, 2006, 2012). In a professional context such as a PLC, agency may be enacted as participants make choices, express ideas and suggestions and take stances concerning work practices (Vähäsantanen et al., 2017). As Biesta, Priestley and Robinson (2015) point out, agency is something people do, rather than a capacity, competence or property they have. For example, Emirbayer and Mische (1998) describe agency as largely shaped by the interplay of social and relational factors: by behavioural components such as a person’s habitual actions, which require their attention and effort, and by internal factors, such as how they go about problematising, deciding and implementing actions effectively under particular circumstances. Vähäsantanen and Eteläpelto (2015) elaborate the concept further by emphasising the significance of an emotional dimension of agency in a professional context. In particular, they argue that emotions which result from the work have consequences for the enactment of professional agency and this enactment leads to further emotions. In this vein, Vähäsantanen and Eteläpelto (2015) stress that agency in a professional context is a multifaceted concept which may relate to making changes, but also to upholding the state of affairs resisting change.

Research methodology

Settings and data set

The data reported in this article derives from PLC conversations recorded in meetings from two separate PLCs, one at a school in Australia and one in Sweden, which the individual authors had an ongoing collaboration about. While our data sets included multiple conversations at these settings (captured over a time span which exceeded a year), for the purpose of exploring how the analytical model might be applied to collegial learning conversations to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences and missing links, we decided to use a small data set which involved a recorded conversation from each respective PLC. Our selected recordings were from late-stage meetings from each PLC, captured at a time when the PLC work was as mature as possible. The two data sets to which we applied the theoretical framework represented two examples of approximately twenty minutes of conversation and reflection among the PLCs about teaching practice. Each recording was made by the respective author, who was familiar with the participants and well immersed in the setting.

Our co-analysis of data from the two settings enabled us to explore how the model might enable researchers to highlight silences and ‘why’ considerations and to challenge the other researcher’s assumptions and interpretations about their study context. The process of collaboratively analysing the data (outlined below) generated a shared set of insights about collegial learning. Working with the analytical process as critical friends also challenged our viewpoints and assumptions about the PLCs and presented alternative interpretations of the data.

Of the two PLCs from which the collegial conversations were captured, the Australian PLC consisted of ten teachers at a primary school in regional Victoria, Australia. This PLC was focused on developing student learning in literacy. The PLC had invited the first author as a critical friend a year before the conversations informing this article were recorded. The other PLC consisted of ten teachers and one principal at a primary school in regional Sweden. This PLC had been working with the second author for two years on developing its professional learning and the impact on student learning through Wenger’s (1998) framework of joint enterprise (content), shared tools and mutual engagement.

Each study involving the two PLCs was conducted in accordance with the Human Research Ethics Committees’ guidelines. Informed consent was gained from the school principals and teachers. All participants were assured that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, without prejudice. The collected data were kept secure, and the anonymity of participants was protected by all their real names being replaced before the data was coded and analysed by the two researchers.

Researcher positionality

As researchers, we were positioned as critical friends to our respective PLCs. As critical friends, our designated roles entailed playing an active role in the conversation by challenging the PLC members’ assumptions about their practice and viewpoints and by asking challenging questions to stimulate reflection (Costa & Kallick, 1993; Swaffield, 2008).

Similarly, the collaboration between us as researchers is a form of critical friendship, in which we seek input from each other to challenge our respective assumptions and thereby stimulate our reflection as researchers. In this vein, we wanted to explore how working as critical friends in a research capacity might offer new insights on each other’s data sets.

Data analysis

As described above, the focus of this article is on exploring how the analytical framework (Svedberg, 2016) with its three core considerations—What? Why? How?—may be used to highlight gaps and clarify silences. This framework was used to co-analyse the selected conversation segments from the two PLCs. As a first step, each author familiarised themselves with the two data sets by individually identifying their initial thoughts and questions, prompted by reading the transcripts.

In the second step of the analysis, we compared our respective thoughts before re-reading the transcripts and coding them in line with Svedberg’s (2016) what-why-how considerations. This process highlighted a different range of ‘what’, as the conversation of each PLC was framed by its unique purposes, values and content. However, the analysis of the PLC conversations revealed common threads in respect to teachers’ descriptions of educational focus points and their use of systematic methods to consider and inform their repertoire of teaching and learning strategies.

The third analytical step entailed synthesising the why-what-how coding with an adapted version of DuFour’s (2004) critical questions. This involved coding for considerations such as what teachers expect students to learn; indications that students have learnt something; teachers’ responses when students have/have not shown that they have learnt something; knowledge needed to advance the progress of students; and changes to teacher practice to improve impact. This phase of analysis generated five categories of data: 1) recognising the need to use data indicating prior learning to inform next teaching steps; 2) scaffolding considerations to manage the learning environment; 3) gathering evidence of learning; 4) processing evidence of learning; and 5) managing organisational considerations. In the final phase of analysis, the data codes were organised into synthesized examples illustrating possibilities and missing links in PLC conversations about purposes, tools and practices to enhance teaching and learning.

Limitations

The findings presented here are necessarily limited in aim and scope, as this is primarily a theoretical article based on two small data sets from two different settings. Nevertheless, we hope that the findings in this article will contribute by offering an analytical model that can be applied to guide critical reflection and collegial conversations for the purposes of developing teachers’ professional knowledge and enhancing student learning.

Findings and discussion

Our application of the theoretical framework to the sample conversations generated four sets of emerging findings. Three of the sets of findings primarily focus on ‘how’ and ‘what’ considerations. The final set outlines the less evident ‘why’ considerations, such as they featured in the collegial conversation samples.

‘What’ and ‘how’: Recognising the need to use data indicating prior learning to inform the next steps of teaching

The most prevalent types of considerations in the sample PLC conversations were teachers raising content related to ‘what’ concerns, combined with ‘how’ issues related to methods, tools and strategies. A key feature in the teachers’ conversations related to the notion of collecting evidence of student learning, which conforms with the notion of using work samples or teaching plans as a common point of collegial conversations (Little & Curry, 2009). Some comments were very specific, such as a colleague noting what particular vocabulary students had used in a lesson (‘what’) and wondering how prior teaching had led to students developing such sophisticated language. The specificity of this query may have been prompted by the particularities of the PLC meeting in which the conversation was recorded. As a result of an earlier conversation in a previous meeting, the teachers at the school had decided to employ a particular strategy, namely, to include short video clips from their own lessons, to help facilitate a shared discussion of practice (what and how) in the subsequent PLC meeting. This initiative appeared to align with the idea of teachers enacting agency by expressing ideas and making suggestions around work practices (Vähäsantanen et al., 2017), which in turn is shaped by the interplay of social and relational factors (Bandura, 2012; Biesta et al., 2015; Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). It also points to the significance of agency, trust and motivation providing the foundation for collegial practice.

While conversations such as this primarily focused on ‘what’ and ‘how’, they implied a ‘why’ (purpose/goal) by inferring that teachers perceived the need to apply data and evidence of student learning to inform their everyday teaching practice. The theoretical framework’s foundational components of trust, motivation and agency also featured when conversations highlighted the potential to develop a shared understanding of each other’s practice within the PLC. For example, some teachers volunteering to film a segment of a lesson enabled an aspect of their practice to be put forward as a discussion point at the PLC meeting. This initiative implies that members of the PLC had a sense of agency and motivation to develop professional practice within the PLC and also that they trusted their colleagues to the degree that they were willing to put themselves in a situation of some uncertainty. In turn, the filming prompted conversations in which colleagues highlighted ‘what’ considerations such as particular indicators of students’ learning they had noted in the clip:

What resonated was just some of the responses, like I was quite impressed with [students aged 5] [able] to articulate vocabulary like “the elephant is sweating”. And Sara asked “why is the title called … ‘the Fun Run’?” So, I was just wondering what support you’ve given them beforehand … (Teacher, Australian PLC)

As indicated in the quote above, by the query about ‘what support’, teachers also sought to clarify ‘how’ aspects of their colleague’s practice, for example, by asking how they sought to promote the learning of particular students, what techniques they employed to assess students’ prior knowledge, or how they had scaffolded prior learning.

As noted above, teachers taking the initiative to film their practice and sharing it with colleagues can be seen as a manifestation of agency, motivation and trust. While the filming of practice and ensuing collegial conversations present possibilities to improve practice, there is also a risk that the conversation becomes overwhelming for the volunteer, who as a trustee is placed in a situation where they are potentially vulnerable (PytlikZillig & Kimbrough, 2016). For us as authors, this realisation became evident through the process of co-analysing the data sets. For example, the conversation illustrated in the quote above, in which a PLC viewed and discussed elements of their colleague’s practice, was perceived by the author embedded in the Australian setting as a positive indicator of trust. This author interpreted the initiative of filming each other’s practice as a ‘how’ response prompted by the PLC teachers being clear about the shared purpose, the ‘why’, although the later was not explicitly articulated. By contrast, during the co-analysis of the data sets, the other author highlighted how they perceived the conversation as potentially confronting for the teacher whose practice was being discussed. This prompted us to reflect on how the theoretical framework helped us clarify missing links or silences in our own interpretations of the data captured at the settings which we are very familiar with. Our ensuing discussion also highlighted the significant role of trust, agency and motivation in underpinning the work of a PLC. Moreover, might these elements constitute the difference between possibilities and silences when sharing one’s professional practice? Previous research emphasizes the need for teachers to feel empowered as professionals, which in turn necessitates that they understand the purposes and motivations for change initiatives (Butler et al., 2011). This would suggest that PLC colleagues need to perceive that ‘why’ considerations that set the direction of the PLC’s work need to be of importance, or else the process of working to realise possibilities will go nowhere. The specific content in a PLC cannot be imposed by outsiders (Banks, 1998; Fletcher, 2019), but is created by those who share questions, concerns, problems and needs (Woods & Macfarlane, 2017). A PLC is also characterised by mutual engagement in procedures, tools, concepts and different ways of acting, i.e., a shared repertoire to illuminate ‘why’ as well as ‘how’ questions (cf. Wenger, 1998).

The application of the theoretical framework to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences or missing links in collegial learning conversations provided several examples where the PLC comments ostensibly articulated ‘how’ or ‘what’ considerations, but implied the significance of trust, motivation and agency. This is illustrated in the quote below, in which the teacher compares methods and content associated with ‘the Maths Boost’ teaching and learning initiative with the current work of the PLC. The teacher’s description of the latter conveys a greater sense of motivation and agency to enhance their own practice.

To my mind, two years ago when we worked on ‘The Maths Boost’ many teachers felt pressured by the set pace. Now we have the opportunity to stop and really examine and drill down in what we want. (Teacher, Swedish PLC)

This quote indicates a sense of ownership and agency, in which teachers enact the possibility to ‘examine and drill down’ to enhance learning. The quote also suggests a motivation to enhance practice by teachers identifying elements of their teaching that they might change to become more effective as teachers and increase the impact of their instruction. These descriptions included gathering and scrutinising the impact of explicit teaching strategies, as well as drawing on peer feedback to identify specific aspects of one’s own practice in order to improve.

In regard to the teachers’ reflection about enhancing student learning as well as identifying those aspects of their practice they might change to increase impact, the quotes above primarily align with our adopted model of Svedberg’s (2016) ‘what’ and ‘how’ considerations. The ‘what’ in the quotes above illustrates content and values that align with the PLCs’ purpose, which is to enhance students’ learning. Closely connected to the teachers’ articulation of purpose were ‘how’ considerations, which refer to particular methods, tools and strategies teachers use as part of their enacted practice in the classroom and as part of reflecting and identifying which aspects of their practice to improve. Both the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ relate to the ‘why’ – the vision, purpose and shared goals – of the PLC. However, in the reflections about teaching practice above, the ‘why’ appears to be implied rather than explicit in the conversation.

These findings from the PLCs point to a connection between teachers’ agency and how important it is for PLCs to clearly articulate ‘why’ dimensions. From a larger perspective, this suggests that when members of collegial groups and organisational structures such as PLCs analyse and unpack the ‘why’ which frames their practice, they simulatenously identify underlying issues and the possible causes of problems within their professional practice, as well as the educational purposes and goals.

Using ‘what’ and ‘how’ considerations to learn ‘tricks of the trade’ from colleagues

The application of the framework to analysing the sample PLC conversations indicated that teachers tended to seek to learn from each other’s practice by asking detailed questions about ‘what’ and ‘how’ aspects of their colleagues’ teaching and learning. For example, several examples of teachers’ practice to monitor students’ learning emerged. These descriptions addressed considerations such as ‘What do we expect our students to learn?’ and ‘How do we know when students have learnt?’ (DuFour, 2004). With regard to the former, examples included ways teachers check that students understand the learning purpose.

… your learning intention was quite long. Could the kids say this back to you? (Teacher, Australian PLC)

Another prominent feature in the PLC conversations was the motivation to learn from each other’s practice in regard to scaffolding and managing the learning environment. As illustrated in the quotations below, this focus was particularly prominent in the PLC where teachers had taken the initiative to take turns in sharing a segment of their lessons.

The things that resonated with me, was [how you included] the posters with the skills, the ‘trying lion’ and the ‘eagle eye’. And I thought using the props was a good thing. (Teacher, Australian PLC)

The quote above with reference to the teacher’s use of props illustrates how the PLC conversation enabled teachers to challenge each other’s practice and assumptions, because another member of the PLC had shortly before suggested that students in the video clip appeared to find the lesson props distracting. Viewed from Svedberg’s (2016) framework, the quotes above suggest that the conversation had a narrow focus, the primary motivation being to explore ‘how’ the PLC members apply a repertoire of methods and strategies to achieve particular purposes. From the perspective of agency and motivation, these conversations (as illustrated by the former quote) indicated teachers’ desire to discuss strategies their colleagues employed to avoid foreseeable or previously experienced pitfalls within lessons.

While the examples above illustrate precision in teachers’ questions, the theoretical framework also illuminated how teachers tended to speak in less specific terms about applying a methodical approach to interrogating practice and processing the evidence of learning.

… one thinks that ‘oh, this will be a huge task, now we’ll have to write 10 pages and submit them. One jumps to those conclusions straight away. That’s kind of the teaching profession, one does and then it’s over and done with, but one doesn’t perhaps reflect on: what did we actually do? Well, we analysed, but we did not use the word ‘analyse’. (Teacher, Swedish PLC)

The teacher who provided the quote above had earlier in the PLC meeting commented that they found the notion of scientific terms such as analysing to be slightly daunting. Their mention above of ‘a huge task’ suggests that they perceived the notion of using terminology and interrogating their teaching practice in the classroom as complex and demanding. However, studying data of how the students performed the task appears to be missing.

The missing link: The ‘why?’

As noted above, the conversations in the two PLCs appeared to focus mainly on ‘what’ and ‘how’, rather than ‘why’. This is not to say that ‘why’ considerations were absent from the conversations. However, when ‘why’ considerations were articulated, they emerged in instances where the topic of conversation related to a broader purpose, rather than specific educational focus points (‘what’) and processes (‘how’).

It appears noteworthy that these broader purposes only really emerged in the third round of analysing the data. While the initial analysis of the transcripts generated a number of examples which the researchers thought appeared to relate to reasons for doing things, the third round of analysis, which was clearly framed by Svedberg’s (2016) definition, generated a smaller selection of qualitative data.

The application of the analytical framework to the two data sets indicated that the purpose of professional learning in both PLCs was change-related in the sense that the intention was to enhance teaching and learning. The analytical framework reflected how the purpose of collegial conversations in the Swedish PLC centred on guided practice in using research tools to enhance the professional practice of the collegial group. This included learning to analyse teaching and learning. One member of this PLC used a food metaphor to describe the purpose of changing their practice to facilitate deep, meaningful and lasting learning, rather than scattered, superficial tips which may be perceived as inspiring, but which lack substance:

… to implement something that is relevant to me and changes me requires a different process. It requires a different process because we love tips and tricks and becoming a little inspired and getting a Facebook update or some such thing, but it’s not ‘fast food’ that gives results. It is ‘genuine nutrition’. (Teacher, Swedish PLC)

The notion of striving to enhance teaching and learning, not just as an individual teacher but using a process to develop collegially a shared culture of practice, was also highlighted:

Well … I think that we have learnt something essential that will help us continue learning. I think that what you are saying is that [insights from action research into practice] must be enacted, it’s always challenging the first time. I think that if we progress with a new module, then the actions will commence more easily. (Teacher, Swedish PLC)

So, it really is essential that we put ourselves out there, that we interrogate what we’re doing. [Turning to volunteer] You know, those wonderings … are pretty good. And you might have the answers … It was … I’m hoping that it will improve your practice. (Teacher, Australian PLC)

While the quotes above appear somewhat vague in respect to articulating an evidence base upon which the teachers’ discussion is centred (Little & Curry, 2009), they reflect the notion that data-based conversations among professionals require the adoption of a way of thinking and challenging ideas that lead towards new knowledge (Earl & Timperley, 2009). As Butler et al. (2011) argue, for a PLC to sustain and achieve its aim of improving teaching and learning, the members need to feel empowered as professionals. Furthermore, PLC members need to understand the aim and underpinning principles of the change initiatives they seek to implement, as they practise and explore ways of integrating and implementing new ideas and learning into their existing practices, structures and processes.

In the wider context, the findings presented in this article suggest that when collegial groups and organisational structures analyse and unpack the ‘why’ which frames their practice, they create a foundation for change which aligns with the core of their practice. By starting with ‘why’, the collegial group initiates the change process by identifying underlying issues and the possible causes of problems within their professional practice. At the same time, they take into account and articulate the educational purposes and goals. Once the ‘why’ is clear and specific, it is possible for teachers to be agentic and align the ‘how/what’ considerations within their teaching practice and for principals to put effective organisational structures in place. From a perspective of change, such an approach enables schools to implement practice that is targeted and likely to be effective, thereby leading to change and enhanced learning and teaching outcomes. Conversely, without first clarifying the ‘why’, PLCs, and schools more generally, run the risk of making changes to practice that put the focus on the ‘how’ or the ‘what’, resulting in ‘quick fixes’ which are likely to lack alignment and be ineffective.

From our long-standing experiences of working with schools, we note that in school development initiatives, in which the intention is to quickly improve academic results, the executive leadership team is frequently quick to articulate how school development initiatives are to be implemented. However, the teachers who are to implement the changes may not be sufficiently included in the process of clarifying what the organisation is seeking to improve or why change is needed. Consequently, there may be a lack of the necessary alignment between the change initiatives and their application to the classroom context and its outcomes in terms of student learning.

We hope that this article, and the framework presented here, may illuminate the importance of enabling collegial conversations to thoroughly address and unpack the ‘why’, before shifting to consider the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of practice—moreover, how this promotes agency and ‘buy-in’, which in turn make approaches to enhancing practice sustainable. We argue that over time, a shared understanding of, and investment in, clarifying the why-what-how considerations has led to a deeper level of collegial conversations, in which there is greater scope to critically reflect on the evidence base and the impact of practice. However, further research is needed to investigate why and how this process strengthens professional practice.

Conclusion

This article explores the use of an analytical model to illustrate possibilities and clarify silences or missing links in learning conversations in a collegial learning context – be it a PLC or a collaboration between researchers.

As outlined earlier, we primarily seek to apply an analytical model to collegial learning conversations for the purpose of illustrating possibilities and challenging assumptions about purposes, tools and practices through using three cornerstones – what, why and how. Secondly, our intention is to explore how this model may provide a lens for researchers who work as critical friends with each other. The model consists of a base with three components (trust, motivation and agency), which underpin three key considerations (what, how, why) that frame a core which is manifested as professional practice, culture, ethos and identity.

The findings indicate that the collegial conversations were most explicit in relation to identifying what elements of practice to improve and how to improve teaching and learning, rather than articulating why change initiatives to develop teachers’ professional knowledge were needed or on what basis they were chosen. The findings may be the result of ‘why’ considerations being self-evident within the PLC and therefore not needing to be made explicit. Conversely, there may have been a lack of specificity in the group’s ‘why’ considerations, highlighting the need to uncover these missing links which frame the work of successful change initiatives which lead to school improvement (Woods & Macfarlane, 2017). To this end, we argue that the ‘why’ dimension constitutes a key ingredient of professional learning conversations. With support from research in the field (Biesta, Priestley & Robinson, 2015; Vähäsantanen & Eteläpelto, 2015) and the emerging implications generated by using the adapted framework from Svedberg (2016) to identify examples in conversations which illustrate possibilities and clarify silences in collegial learning conversations, we posit that ‘why’ considerations may influence people’s sense of ownership in implementing change initiatives, which in turn shapes how they negotiate the ‘how and what’ of their work. Secondly, the silences in the conversations indicate that all three considerations (what-why-how) are needed to reify changes and improvements to teaching practice and students’ learning outcomes. Thirdly, our application of the theoretical framework suggests that by explicitly taking ‘why’ considerations into account, the possibilities of collaborative approaches to improve practice and challenge assumptions about purposes, tools and practices become more focused.

Our findings suggest that at times the analysis by teachers of evidence of learning outcomes is more focused on teaching activities than on student learning. Furthermore, lack of clarity about ‘why’ considerations may reduce teachers’ professional identity by positioning them as implementors of the ‘how’ suggestions of others (cf. Butler et al., 2011).

This article seeks to contribute by offering insights to both teachers and researchers who engage in collegial learning conversations and who may employ the theoretical framework presented here to guide the design of practice development which is built on ownership and mutual engagement. Our research collaboration has entailed us embracing the role of critical friends in a research capacity, which can be seen as both an asset and a challenge, a balancing act between closeness and distance. We have fostered a close working relationship, yet have at the same time adopted a stance of distance by critically examining the PLC conversations that our research is grounded in. We note that ‘why’ considerations in the context of professional learning conversations may be perceived as threatening (particularly if directed to an individual, rather than the group), unless there is an element of closeness to contextualize the content. On the other hand, distance from the context may help the researcher realise that ‘why’ considerations need be made more explicit in the context.

The findings presented in this article indicate that researchers who work with PLCs as critical friends need to employ different tools to analyse practice together with the participants. In this case, we analysed practice using a what-why-how lens and related it to our conceptualization of a professional group identity based on motivation, trust and agency. We propose that this approach may provide helpful guidance to PLCs working to improve their practice by using a framework to clarify and analyse the underpinning purpose and goals which set the direction of their professional practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the teachers and schools they collaborate with, without whom the research reported on here would not be possible.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have not received funding for the research reported and declare that no potential conflict of interest is associated with the study.

About the authors

Anna Fletcher

(Orcid ID: 0000-0003-1248-9838), PhD, is the Associate Dean Teaching Quality in the School of Education at Federation University Australia. Her research expertise and publications address three areas: 1) student agency, achievement and self-efficacy within classroom assessment from a perspective of social cognitive theory; 2) practitioner research and teachers’ capacity building; and 3) the role of education to build human capital in place-based contexts. Anna represents Federation University on the Australian consortium of fifteen universities developing and implementing the Graduate Teaching Performance Assessment (GTPA). She has instigated research partnerships at local, regional and international levels (particularly with Scandinavia).

Ann-Christine Wennergren

, PhD, is Associate Professor in the School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Halmstad University, Sweden. Her main research interests are based on partnerships between schools and the university concerning tools and structures for teacher professional learning and school improvement.

References

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. doi:10.2307/40212163

- Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. doi:10.1177/0149206311410606

- Banks, J. A. (1998). The lives and values of researchers: Implications for educating citizens in a multicultural society. Educational Researcher, 27(7), 4–17. doi:10.3102/0013189X027007004

- Baskerville, D., & Goldblatt, H. (2009). Learning to be a critical friend: From professional indifference through challenge to unguarded conversations. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 205–221. doi:10.1080/03057640902902260

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Butler, H., Krelle, A., Seal, I., Trafford, L., Drew, S., Hargreaves, J., Walter, R., & Bond, L. (2011). The critical friend: Facilitating change and wellbeing in school communities. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Coates, M. (2017). Setting direction: Vision, values and culture. In P. Earley, & T. Greany (Eds.), School leadership and education system reform (pp. 90–99). Bloomsbury.

- Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(10), 49–51. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=9401101278&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Curry, M. (2008). Critical friends groups: The possibilities and limitations embedded in teacher professional communities aimed at instructional improvement and school reform. Teachers college record, 110(4), 733–774.

- Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3/4), 325. doi:10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

- DuFour, R. (2004). Schools as learning communities. Educational Leadership, 61(8), 6–11.

- Earl, L. M., & Timperley, H. (2009). Understanding how evidence and learning conversations work. In L. M. Earl & H. Timperley (Eds.), Professional learning conversations: Challenges in using evidence for improvement (pp. 1–12). Springer.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023.

- Fletcher, A. (2019). An invited outsider or an enriched insider?: Challenging contextual knowledge as a critical friend researcher. In S. Plowright, M. Green, & N. F. Johnson (Eds.), Educational researchers and the regional university: Agents of regional-global transformation. Springer.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2009). Teacher professional learning in an age of compliance: Mind the gap. Springer.

- Hedges, H. (2010). Blurring the boundaries: Connecting research, practice and professional learning. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(3), 299–314. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2010.502884

- Jacobsen, A. J., & Buch, A. (2016). Management of professionals in school practices. Professions and Professionalism, 6(3). doi:10.7577/pp.1503

- Kincheloe, J. L. (2012). Teachers as researchers: Qualitative inquiry as a path to empowerment. Routledge.

- Little, J. W., & Curry, M. W. (2009). Structuring talk about teaching and learning: The use of evidence in protocol-based conversation. In L. M. Earl & H. Timperley (Eds.), Professional learning conversations: Challenges in using evidence for improvement (pp. 29–42). Springer.

- Loughran, J., & Brubaker, N. (2015). Working with a critical friend: A self-study of executive coaching. Studying Teacher Education, 11(3), 255–271. doi:10.1080/17425964.2015.1078786

- PytlikZillig, L. M., & Kimbrough, C. D. (2016). Consensus on conceptualizations and definitions of trust: Are we there yet? In E. Shockley, T. M. S. Neal, L. M. PytlikZillig, & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on trust: Towards theoretical and methodological integration (pp. 17–47). Springer International Publishing.

- Samuelsson, K. (2018). Teacher collegiality in context of institutional logics: A conceptual literature review. Professions and Professionalism, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.2030

- Svedberg, L. (2016). Pedagogist ledarskap och pedagogisk ledning [Pedagogical leadership and pedagogical guidance]. Studentlitteratur.

- Swaffield, S. (2008). Critical friendship, dialogue and learning, in the context of leadership for learning. School Leadership & Management, 28(4), 323–336. doi:10.1080/13632430802292191

- Swaffield, S., & MacBeath, J. (2005). School self-evaluation and the role of a critical friend. Cambridge Journal of Education, 35(2), 239–252. doi:10.1080/03057640500147037

- Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004

- Vähäsantanen, K., & Eteläpelto, A. (2015). Professional agency, identity, and emotions while leaving one’s work organization. Professions and Professionalism, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.1394

- Vähäsantanen, K., Paloniemi, S., Hökkä, P. K., & Eteläpelto, A. (2017). An agency-promoting learning arena for developing shared work practices. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 351–371). Springer International Publishing.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice, learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

- Woods, D., & Macfarlane, R. (2017). What makes a great school in the twenty-first century? In P. Earley, & T. Greany (Eds.), School leadership and education system reform (pp. 79–89). Bloomsbury.

- Wright, N., & Adam, A. (2015). The ‘critical friend’ role in fostering reflective practices and developing staff cohesion: A case study in a new secondary school, New Zealand. School Leadership & Management, 35(4), 441–457. doi:10.1080/13632434.2015.1070821

- Zimmerman Nilsson, M.-H., Wennergren, A.-C., & Sjöberg, U. (2018). Tensions in communication – teachers and academic facilitators in a critical friendship. Action Research, 16(1), 7–24. doi:10.1177/1476750316660365