Introduction

Considerable attention has been directed towards participatory research, displaying a broad spectrum of research ambitions in social work as well as in other disciplines, from action research (Eikeland, 2012; Westoby et al., 2019) to community-based participatory research (Donnelly et al., 2019) and practice-oriented research (Frid, 2021; Sørensen & Wilms Boysen, 2021). This article contributes to the discussion about community-based participatory research (Donnelly et al., 2019) and about the researcher’s own attachment to the place of research.

Community-based participatory research inevitably actualizes the importance of place, both the physical place and the mental notion of the place in which you live and work. A previous study of voluntary social work and its capacity for value creation in relation to ideas about place and the people in that place (Elmersjö, 2020) stresses, from an urban theoretical approach, the importance of geographical area in terms of understanding the relationship between a society and the people living within it. A study of the impact of civil society in socially marginalized areas (Kings, 2011, p. 141) discusses how a place and its users co-produce each other, and illustrates how homemaking, trust and belonging to specific areas are characterized by socio-economic challenges. Similarly, Holmqvist (2015) and others (Blunt & Sheringham, 2018; Hörnqvist & De los Reyes, 2016; Papakostas & Gawell, 2021) show how place can influence people’s welfare, depending on the place they are in and their perceptions of that place. In connection with the idea that a place and its inhabitants are co-producers of each other, we are interested in the impact of place on the researchers’ own learning about place and their place attachment processes. The context of our study is a municipality in the Stockholm region that is becoming increasingly polarized and spatially segregated, specifically in relation to an ongoing study of homemaking, belonging, and the significance attached to a place by older people who live there and the professionals who work there.

A socially engaged academy and the researchers’ own place attachment

A central ideal in research is publication in peer-reviewed journals on subjects related to current research debates in a wider international research context, commonly published out of reach of the communities to which the research may be relevant (see Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al., 2019). Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al. (2021) argue that a socially engaged academia has an important civic role to play at a time of changing conditions for social work: a time of social change and civil society involvement in the ‘glocal’ – the intersection where the local, national and global are intimately entangled (see Hartley & Harkavy, 2010). Central here is the role of the committed researcher, and the various contextual conditions that characterize the relationship between the socially engaged academic and the local community. Different forms of partnership between local communities and universities are discernible in descriptions of socially engaged academia, but most commonly social justice is ‘the why,’ ‘co-learning’ is ‘the what,’ and action research is ‘the how’ (cf. Rutherford et al., 2011).

There is an increasing interest in and recognition of partnerships between local communities and academia as a strategy for creating social change. Participatory research is also anchored in the European Commission’s research policies (Hultqvist, 2021), which has led to a greater focus on participatory research concerning policymaking and knowledge and innovation strategies (Macq et al., 2020). According to Fitzgerald et al. (2010), a partnership requires that the voices of both researchers and local community partners are heard. The experiences of both partners, the lessons learned, and the knowledge produced are vital if the partnership is to be developed further. This reinforces the importance of social responsibility with reference to place. The room for manoeuvre for a socially engaged researcher depends on various contextual conditions and puts further demands on the academic to act as a ‘responsible institutional neighbour’ for society (Hartley & Harkavy, 2010). This can be embodied in community-based research, in which researchers, together with practitioners and service users, produce knowledge that is of practical use (Kemmis, 2009). The active participation of local inhabitants, community organizations, and representatives in the place at all stages of the research process – from problem formulation to the dissemination and implementation of research results – is central. However, since the partnership aims to achieve mutual benefits for all those involved, it is also important that the research and the researchers contribute to community development.

To establish mutual trust between researchers and research participants, central factors are the researchers’ genuine involvement in the place and a shared sense of belonging with the participants, and thus also the researchers’ own place attachment processes. This is in line with the ideas of early social work practice, notably the settlement movement (Addams, 1912). From the perspective of the settlement movement, for social workers to reach marginalized groups they must become part of the community and work together with community members to achieve community development, belonging and inclusion. This place-based social work stresses the social workers’ own experiences of the place they are working in, and in the long run the social workers’ own place attachment. In our study, the exclusion of older people from social society, often based on ageism, makes them a marginalized group. This may be seen from our own research as well as that of other researchers. For example, Walsh et al.’s (2018) scoping review reveals that while there are grounds for a scientific focus on old-age exclusion, there is not enough research being done on the topic. Additionally, Krekula (2021) and Snellman (2021) reveal the consequences of ageism, such as health problems and inequality, and the need for more explorative research.

Notions of place attachment were first developed within environmental psychology, stressing how emotional bonds are formed between people, places and physical surroundings (Plunkett et al., 2018), and also include memories (Alawadi, 2017). To be place attached means to have an identity that is connected to a place – a place identity with a sense of self, based on the places in which one’s life is spent (Fullilove, 1996). This is an important base for local personal engagement and involvement (Estrella & Kelley, 2017). Place attachment has therefore been said to have an impact on community development and social community capacity (Plunkett et al., 2018), and to be valuable in promoting socially responsible behaviour and civic engagement (Estrella & Kelley, 2017). Place attachment is about simply being in an area or actively using a place in different ways (Riolo, 2020). The notion of place attachment as ‘doing’ is closely connected to the notion of place as “place-in-process” (Thrift, 2008), the result of a constant reinvolvement process based on the continual redefinition and reconstruction of the meaning of a place (Cristoforetti et al., 2011).

Belonging can be interpreted as a resource on which people may draw in terms of the local politics of place (Stratford, 2009). A socially well-functioning community is one that allows residents to ‘put down roots,’ form place attachments and create bonds of mutual support with neighbours (Manzo et al., 2008). This can be contrasted with various forms of ‘distressed housing,’ or displacement and dislocation from home (Manzo et al., 2008). If belonging is associated with connection and an attachment to place, the contrasts to belonging include social and ecological dispossession and displacement (Stratford, 2009). Fullilove (1996) notes that place attachment is something that “parallels, but is distinct from, attachment to person, is a mutual caretaking bond between a person and a beloved place,” which can be threatened by displacement (Fullilove, 1996, abstract). When exploring the meaningful bonds that people have with places, such as relationships with socio-physical settings, Masso et al. (2008) stress the importance of exploring people-place bonding processes under conditions of displacement or dislocation.

Displacement and dislocation from home are most explored in the context of forced relocation (Afriyanti et al., 2021; Manzo et al., 2008). Forced relocation is something that complicates residents’ attachment to their new place (Afriyanti et al., 2021; Manzo et al. 2008; Thurber, 2021). It is also something that disrupts the “fundamental social processes necessary for optimal community functioning” (Spokane et al., 2013, abstract). Deboulet and Lafaye (2018, abstract) note that “displacement can be considered as an eviction process, traces of which in different ways still have resonance long after tenants have been placed in their new social housing.” Similarly, in the context of forced migration, Kale (2019) notes that “important people-place relationships are often severed during forced displacement, leading many refugees to feel a sense of loss, grief, and disorientation which can negatively impact upon their wellbeing and hinder their resettlement in a new country” (Kale, 2019, abstract). In addition, neighbourhood and community social capital, collective efficacy and place attachment are social processes that may be compromised following natural disasters, conflict, and upheaval (Spokane et al., 2013). Gentrification is not just about residential displacement and the loss of affordable housing. Gentrification can also disrupt feelings of attachment and belonging even if residents have lived in a place for a long time (Valli, 2015), and may also displace community histories, social ties, and spaces of cultural gathering and civic action (Thurber, 2021).

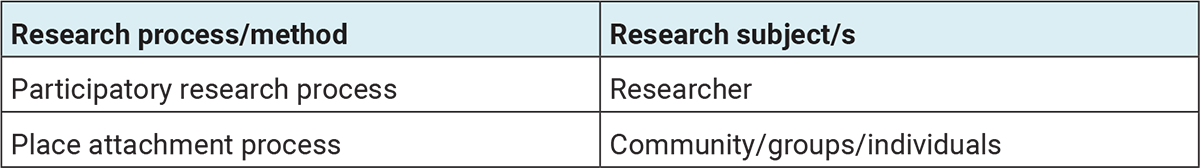

We argue that socially engaged research is not only about partnership with the community but is also in line with the ideals of a place-based social work practice as conditioned by the researchers’ own place attachment. Drawing on the Settlement movement and the tradition of social workers being in place, we stress both the importance of the researchers’ place attachment and the disadvantage of the displacement and dislocation of researchers from the research place. In sum, this shows the importance of the four related themes set out in Figure 1.

Methods

Our data for this article comprises notes, observations and diaries. Both the data collection and the writing involved an iterative people-place bonding process, during which we gradually got to know people in the municipality through active use of the place (Riolo, 2020). Following the dictates of our own curiosity and competence requirements, this involved Zoom meetings and telephone calls, walking or cycling and arranging coffee meetings and picnics, as well as participating in more formal board meetings in the municipality. These activities were done either on our own, or together with older people living in the municipality and professionals working there. We also examined websites offering flats for rent or purchase in the new parts of the municipality, in order to get a sense of the cost of living and the ease of getting a flat, and to look more closely at the presentation of new housing in the area and how it is marketed. Our experiences of the place of research are affected by it being situated in a particular part of northern Stockholm, which is a part of Stockholm different from our respective home communities and the place of the university where we work. We started to refer to the process of data collection as ‘winding’ or ‘following the clouds,’ dependent on our conversations with professionals and older people, but also referring to our own sensory experiences of the place. Similarly, our own analytical processes took the form of ‘place attachment storytelling,’ which involved us telling each other different stories about and our experiences of the place, and through this storytelling supporting each other’s place attachment process.

Hanna came on her bike the first time we met up at the place in order to get a physical/sensory sense of the place and its surroundings (see Costa et al., 2014). Experiencing the distance between the place and her own home community contributed to the place attachment process. There was a sense of time and of the tiredness in her legs. It took almost two hours to reach the place by bike from home, mostly due to a lot of wrong turns, resulting in her being very late for the appointment with Magdalena. Hanna experienced the wind and the scents of a showery late spring day. She also experienced the different neighbourhoods in terms of the social and physical environments she needed to cross in order to reach the place, as well as taking a lot of wrong turns along the way, getting lost due to several areas of affected by the construction of new neighbourhoods, new roads, a new subway route and new station for the commuter trains. She interpreted this as “the place as a place in rapid/intense transformation.” This was later referred to by the participants in the study as consisting of both ‘old’ areas, as one of the oldest suburbs of Stockholm, and ‘new and emerging areas,’ as part of a new greater Stockholm area emerging due to increased national and international immigration. The same description of old and new together in one place worried the professionals we spoke with. They often raised the risk of place dislocation and what needed to be done in order to make new citizens feel at home in the new neighbourhoods.

The need to support new citizens with no previous or contemporary community history during their relocation to the newly constructed areas was described as a task for both professionals and citizens, but also for the ‘old’ place. The plan is that the ‘prehistoric community’ history will participate in the new ‘storying’ of the place. This stresses the need to connect with or produce a new place history from the prehistory of the place in order to avoid dislocation. For example, the community website connects the newly constructed place with both a ‘prehistoric community’ from the Swedish Bronze Age (1700 BC to 500 BC) and a modern industrial history as a place for modern Swedish military and civil aviation since the early 20th century: “Prehistoric burial grounds and settlements for airfields for both military and civil aviation. (…) Settlements, burial grounds, rune stones and other ancient remains show that people have lived here since the Bronze Age” (municipal website).

The main idea for the entire project is the vision of a single, cohesive city – Stockholm, the capital of Sweden – that at the same time acknowledges the need for everyone’s own space, a place where you know your way around, where you have neighbours and feel safe, the starting point of your everyday life and a place where you can recover yourself on a regular basis. In our conversations with municipal officials, questions concerning aspects of safety, belonging, place attachment, and trust were naturally framed as municipal obligations for securing the quality of life of the people living in the area. In the study, we got to know older people in the area and to learn in more detail about these aspects of everyday life. Not being the ones to define aspects of neighbourhood, such as safety, belonging, place attachment, and trust, was an important part of our participatory process. Instead, a core methodological path was talking about, listening to and to some extent the sharing of stories, ideas and reflections with municipal officials and people living in the area.

Our first meeting in the project was with municipal officials whom we had invited to talk about our study. At this meeting (described below), we presented our exploratory design and our view of it as ‘empirical responsiveness’ and ‘organically driven.’ We also presented ourselves and our experience of research on societal conditions regarding older people and people with disabilities, as well as our stand on socially engaged research. We believe that it was important to be clear about this early on, and about the collaborative conditions of the project. Drawing on earlier participatory studies (Elmersjö, 2021; Hultqvist, 2021; Macq et al., 2020), we also believe that an explorative design in such a collaboration is an important tool for achieving participation and deliberative processes. In addition, we believe it is important for an organically driven research process to grow continuously, both relationally and in terms of knowledge. However, this process also risks making participants anxious, uncomfortable, or uncertain about their roles and about the future of the project. Time and commitment are often at a premium, and working life today is about priorities (cf. Elmersjö et al., 2022). It was therefore important to clarify our responsibility for keeping track of the project’s progress and processes through documentation and following-up on knowledge issues and relations.

Taken together, the data consists of conversations with municipal officials in one municipality in the Stockholm region. We spoke to nine officials with different functions in the municipality about matters concerning the situation of older peoples in the municipality and/or tasks concerning place development and place sustainability. We also met, shared stories with and walked and talked with groups of older people in two different constellations: board members of the local branch of one of the largest organizations for retired people in Sweden, and a mixed group of older people from two different Christian communities. With few exceptions, all the older people we met were white Swedes. Some of them had lived in the municipality for most of their lives, while others had lived in different parts of Sweden before settling down in the municipality. The data also includes our reflections on learning about the municipality and physically experiencing the community and place.

Findings

In our study, the older people and the professionals talk about place in relation to their sense of belonging. The older people talk about place in relation to being able to feel at home in times of change – both changes of place and changes in population. The professionals talk about being able to separate the professional self from the private self that lives in the community, or the dislocation (good or bad) for the professional living in other municipalities than the one in which they work. At the same time, we as researchers became aware of the importance to us of gaining knowledge of the place we were investigating in a Settlement sense (Addams, 1912). The ideals of place-based social work practice of living in the area were not possible for us, but being present ‘body and mind’ in the area and ‘making it our place’ became essential to understanding how a sense of belonging can change over time.

We elaborate below on the different methodological aspects of the researchers’ own place attachment process within the research process, and the benefits gained.

Following the clouds

Our starting point for the first conversation with officers from the municipality was the theme “homemaking, belonging and the significance of place for older people.” We presented our standpoints on the project and stressed the ambition inherent in our approach to work together with them, rather than just invite them to participate in a set research design.

This relatively open start to the discussion enabled the participants to bring in their point of view and ‘fill in the blanks.’ The conversation raised questions and provided tips for gaining more knowledge on the subject. We all addressed the concept of ‘life between the houses,’ which stresses the importance of neighbourhood. All the participants agreed on the need for a second meeting and notes taken during the meeting were emailed to the participants. To provide an open climate for discussion and avoid any potential steering effect from a descriptive and detailed text, we decided to produce an image of colourful clouds. Each cloud had various tips and suggestions for people to contact or places to visit so that both researchers and municipal officers could learn more about marginalized groups, neighbourhoods, and community work in the municipality.

This stance, both inclusive and explorative, taken at our first meeting with municipal officers, perhaps challenged the perceived role of researchers in municipal projects as primarily conducting evaluations. In that role, the researcher presents a formal and structured research design and delivers a research concept, followed by a result – the evaluation. Such a process legitimizes the role of the researcher and maintains the relationship between researcher and research object as a two-way relationship. We relate our way of thinking about research to Frid’s (2021) contribution on an intra-active action research approach. Residing in the complexity of practice is about trying to stay immersed in the muddle; what Donna Haraway (2016) has referred to as “staying with the trouble.” We embrace practice as non-fixed and not limited to human relations (cf. Frid, 2021, p.29). Research and practice as well as place will affect each other and ongoing opportunities for change will arise. In this fluid process knowledge production grows out of closeness, and in our case closeness is partly about us as researchers being in, learning about and identifying with the same place as the other participants.

In the meeting referred to, we exemplified our research competence by sharing our research interests, our experience of similar research projects and our knowledge of different groups in society. Our domain-specific expertise was clearly expressed: Magdalena as a social worker by profession and a researcher who focuses on eldercare; and Hanna as a researcher in the area of disability studies. We also discussed our experience of working with action research methods.

Drawing on Sørensen and Boysen (2021), it is possible that our expressed domain-specific expertise served to strengthen the co-creation process. The risk of this design, as we see it, is that it brings with it some form of insecurity for both researcher and research object. Overall, however, a non-fixed qualitative research design naturally opens up to different methodological paths ahead. Discussions about the next step will move back and forth to a greater extent, and it is possible that several meetings will be needed. This also brings up the element of time: an explorative design takes more time for both researcher and participants. Showing respect for those working in social services and the work itself is partly about respecting limited time available to the former and using their participation carefully (cf. Elmersjö et al., 2022). However, it became clear at our meeting that we as researchers would be the ones to make appointments and schedule meetings, after checking dates with the participants. In this way, we became the administrators who removed from the rest of the participants the administrative burden of being the person who makes it happen. This was important for everyone and reinforced the time aspect. Making room for research is not only about interest, engagement, ability, or opportunity. It also demands a sort of service that will smooth the research process. In addition, by taking on the administrator role and positioning ourselves as knowing very little about the municipality at the beginning of the project, we acknowledged their expertise on the subject, including about what interesting research questions to pursue.

To some extent, following the clouds and focusing on our place attachment as researchers transformed the researcher and participant roles in the research project. Since we as researchers acknowledged both the need and the responsibility for place attachment, the roles of participant and researcher, as giver and receiver, were transformed. This was a game changer for the project as a whole, as from early on it changed the power relations between the different roles.

The five senses path

The Stockholm region, which is the largest metropolitan area in Sweden, is divided into 13 administrative districts and 23 municipalities. Both researchers grew up in the Stockholm region, but had little experience of the municipality involved in the project. Early on in our research process we found ourselves talking about and trying to understand a municipality we knew very little about. It was not enough to learn about the place through the experiences of other people, such as municipal officials and the participants themselves, or to read and learn about the history of the place. We wanted to be there, seeing for ourselves, smelling, touching, feeling, listening and even tasting the place. The five senses became our knowledge path, which we experimented with at the Garden of the Senses in the centre of Stockholm.

During one of our early meetings with the municipal officers, one of them told us about a garden in the city of Stockholm that had provided a model for a smaller garden at a residential care home for older people in the municipality. We were also given the contact details of a member of the social board who had been involved for many years in creating a green community for all, but especially for older people in need of care.

In our dialogue with this member of the social board, we learned much about his vision of what we interpret as green accessibility from an ageing perspective. We were introduced to his vision of a ‘garden of the senses’ in the municipality and decided first of all to visit the model for it in Stockholm. This was important to us as researchers; we needed a more detailed knowledge of the garden, seen as a model for future projects in the municipality. We went to experience it for ourselves, with our five senses and a mindset focused on learning as ‘a whole being.’ To be able to do this, we formulated a simple schedule for embracing the five senses experience. A first step in this procedure was to acknowledge the burden of everyday life and the risk of thinking about everything else but the garden: “What does our everyday life bring with us?” One of the final steps in the procedure was to acknowledge what had happened to us in the garden: “What did the garden bring to us?”

At the Garden of the Senses in Stockholm city, using our own five senses in the observation of place came naturally to us. We had recently conducted an experimental composting project, which explored the relationship between mind, body, and soil. That experience made us attentive to the potential power of mind, body and place. However, we also noticed how easily we became practical, rational and effective even in such a project. The compost project also stressed the importance of acknowledging the time aspect, by which we mean that exploring the relation between senses and place takes time. We found conducting the observation to be a rewarding and well-structured method for putting ourselves as researchers in the place and examining how we experienced the garden as a space for both body and mind. Following this first observation in the Garden of the Senses we continued to use the five senses method in our research process.

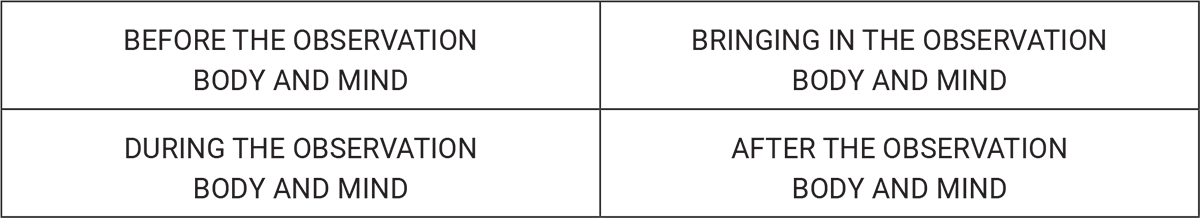

The five senses observation map has four parts (see Figure 2). The different parts assist the process of becoming aware of body and mind in order to recognize what happens in a place. The five senses capture the wholeness of body and mind, helping you to recognize what happens when you focus on smell, sensations, vision, hearing, and taste. In our research, following the five senses path involved a collating our experiences. Therefore, directly after the observation, we sat down nearby and talked about our experiences during the observation and jointly developed our understanding of place. We then separated and went home to write up notes that we later shared with each other. The notes varied and of course mirrored our personalities and our perceptions of the world. In one example of an observation note, Magdalena noted that it was:

Almost as if it is difficult to experience the park itself because there is so much sound, life and movement from the surroundings. Also, the liveliness outside the park makes the park appear frozen. It feels a bit like stepping into something frozen. Locked in a snapshot. (Observation notes, Magdalena)

Magdalena perceived the garden as “something frozen” in relation to the noise outside the park (where there was a playground). However, someone else might describe the garden as an oasis, a quiet, safe spot that hides a person from the outside world. Having at least two researchers in the research project made it possible to let our observations merge to some extent, and to exchange sensory experiences. It also provided an opportunity to see ourselves using the other as a mirror, and to think about what we had experienced. Our experiences also brought us closer to each other as researchers and fellow human beings.

After bringing all the notes together, we added new thoughts based on our readings of them until the observation was perceived as saturated. The notes were therefore collective rather than individual field notes, and together they constituted the results of our place attachment storytelling. This also shows how the observation maps bring structure to observations.

As is stressed above, place attachment has been conceptualized as attending or using a place (Riolo, 2020), and as ‘place-in-process’ or the emerging results of constant reinvolvement processes based on a continuous redefinition and reconstruction of meaning (Cristoforetti et al., 2011). Following Alawadi (2017), our place attachment was concerned with bonding with physical settings, creating memories and to some extent being part of relational processes (meetings, talks and events) using our five senses path to knowledge. Visiting two gardens of the senses, one in central Stockholm and the other in the urban area of the municipality, served several purposes. Firstly, it trained our ability to connect to our five senses and to view experiencing our world with our five senses as opening up for a more complex researcher understanding of our surroundings. Secondly, we observed the two gardens of the senses and reflected on their function and their impact on us and the people around us.

Sharing experience of place and place attachment

Our study involved conversations with people with different access to and experiences of place in the municipality. Unlike regular interviews used to obtain information, the conversations in our study aimed for shared and collective knowledge production as co-learning.

Co-learning is not just about gaining more knowledge about a phenomenon, place, or subject. It is about mutual self-development and learning relationships between the researcher and the participants in a study. Our five senses path for gaining knowledge in the research process, which was something we gradually grew into, had several turning points. The first happened before we had even formulated the five senses path: Going with an explorative research design. This approach to data collection resembles snowball selection but is a more widely defined approach that comprises not only the recruitment of participants, but also a way of collecting data. We think of this as being what we started to refer to as ‘following the threads,’ or the yarn of experiences. Both researchers had similar experience from previous action research projects: Magdalena from a project in which the research questions were formulated with employers and volunteers in an NGO in a suburb of Stockholm; Hanna from a project in which she was a follow-up researcher with a group of autistic people, and in which both researcher and participants formulated threads of interest to discuss in focus groups during the period of data collection. In the latter part of these projects, the themes from the transcripts of the data that were found interesting enough to be analysed in greater depth were identified jointly with the group. In general, the focus of both previous action research projects was on filling knowledge gaps and learning about the needs and wishes of the participants in the research. In the current study, the research experience as a whole came to be much more about following the clues to a broader understanding of the needs and wishes of the community. This became important in relation to achieving an overall social political understanding of the welfare state, particularly in connection to eldercare and disability care.

During the first meeting with the municipal officers, several different threads started to appear. These threads were followed up in new meetings with people suggested by the municipal officers. These meetings in turn led us further, with new suggestions of people to talk to and subjects for conversation. Working thematically and in an exploratory way meant letting go of fixed research questions and being responsive to empirical findings as we went along. We were positioned differently in different interactions; sometimes an ‘interesting’ or ‘nice’ person to talk with, or ‘young female company,’ sometimes as a possible pathway to politicians’ ears, as a bridge between residents and professionals/municipal officers, or between municipal officers from different municipal areas. The research participants became not only bearers of knowledge for us to digest, but also active agents driving the project based on their own knowledge interests or what they found interesting to talk about or share with us. As researchers we started to do things together with the participants, following them sometimes as more passive listeners and facilitators of the conversation, or as participants in walks and coffee meetings. Sometimes we listened to what was said and asked questions to facilitate the discussion. At other times, we steered the conversation more actively towards themes we found particularly interesting that had evolved from the conversation or experience sharing. The conversations were allowed to swing back and forth in directions that we and the participants found interesting. (For a similar shared interest-based approach to research interviewing/conversations, see Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, 2019.)

‘Walk and talk meeting’ with a group of older people

The following is based on Magdalena’s recall of her experiences at a ‘walk and talk’ meeting with a group of older people, which both she and Hanna participated in. Hanna has woven some recall of her own into the text. The walk and talk method was inspired by walking narrative methods, especially drawing on the landscape research of Costa et al. (2014). We used this approach to get away from ‘consuming the participants’ and ‘learning as much as possible.’ Instead, we wanted to slow down and perceive the place with them. At the same time, we wanted there to be storytelling in an organic way, allowing participants to guide us and share memories of place as we walked together.

Just as the summer of 2021 was preparing to bloom, we went on a walk and talk with a group of seniors who all belonged to different denominations. We were invited to the group meeting by one of the members and they were all very welcoming. Neither Magdalena nor Hanna had met the people before and we had very little experience of the community at this time. Being able to connect with people you have never met with an open mind and body, and being able to make yourself a part of something new is as much about letting go for the moment of yourself, your needs and your feelings, your wishes and problems. In our social work programme at our university, this is part of an educational training module referred to as “personal and professional development” (PPU). Recently, both authors have introduced PPU as part of a PhD course, given that the need for self-knowledge and the ability to be aware of your needs in order to be able to put them aside is as important for PhD students in social work as for students on the social work programme. Now, in the municipality, we had the chance to practice our own theory. The five senses path for knowledge was useful, not only for structuring data about our own learning in the participatory process, but also for making us ready for the task and helping us to pay attention to what we brought to it, in our minds and our bodies.

The walk and talk meeting was itself a typical experience of being part of something new and unfamiliar, not knowing what would happen or what was expected of you. As a researcher, you are both exposed and challenged. Besides talking to strangers without a given theme, Hanna and I were put on stage and asked to answer all possible questions linked to our research project and the politics of eldercare. Our unstructured research design left it open for the group to interpret themselves and us, and throughout the meeting we were constantly positioned differently in different interactions – sometimes as ‘interesting’ or ‘nice’ people to talk with, sometimes as a possible pathway to politicians’ ears.

Concluding reflections

This article has explored what the researchers have learned about place and their attachment to place in connection with an ongoing study on homemaking, belonging and the significance of place among older people. One of the lessons learned about the researchers’ place attachment is that the value of time spent in a place is central to embracing (the) place and being fully part of the participatory process as a researcher, as well as bringing truthfulness to participatory work with municipal officers and marginalized groups in the community. The importance of the researchers’ place attachment is linked to the act of being together, and to developing methods for, and theories about, participatory research with particularly vulnerable groups in society. In order to fully embrace PAR through co-writing and co-collecting research data, this ‘togetherness’ sheds light on the importance of not only ‘getting something from’ but also actively ‘giving back to’ the community. This involves participatory elements of community-based and practice-oriented research (Donnelly et al., 2019). In our study, this was done by the participants giving us tips and suggestions about people to contact or places to visit in order for both researcher and municipal officers to learn more about marginalized groups, neighbourhoods and community work in the municipality. In this process, the older people became our co-learners; they taught us about the place, and we responded to their questions concerning eldercare politics.

The ‘giving back’ must occur in ways that are most helpful for the participants involved, and perhaps also most practically useful (cf. Kemmis, 2009). Similarly, physical proximity and social interconnectedness have the potential to be important in strengthening aspects of safety, belonging, and place attachment as vital aspects of enhancing the life quality of the people living in the area. However, achieving authentic partnerships can be difficult (Fitzgerald et al., 2010), and not being the ones who defined aspects of neighbourhood was an important part of our participatory process. Talking, and the receiving and sharing of stories, ideas and reflections with municipal officials and people living in the area formed the core methodological path. In addition, we believe it is important for organically driven research processes to grow continuously, both relationally and in terms of knowledge. Practice and theory played a central role in the collective learning based on people’s experiences (cf. Eikeland, 2012).

However, this process might risk causing increased anxiety among both researchers and participants, by making them uncomfortable and uncertain about their roles and the future of the project. Time and commitment are expensive, and life today is often about priorities. Clarifying our responsibility to keep track of the project’s progress and processes, through documentation and following up on knowledge issues and relations, was therefore very important. Unlike regular interviews for gaining information about something, the conversations in our study aimed at shared and collective knowledge production on place. The benefits of the conversations were the potential for co-learning. Co-learning is not just about gaining more knowledge about something. It is also about mutual self-development and developing learning relationships between the researcher and participants in the study.

While the distinction between home and place often includes notions of a division between private and public, we assume, in line with Blunt and Sheringham (2018), that home and place (in this case the municipality) are interrelated. How people concretely draw boundaries between home and their immediate surroundings is fluid and depends on socioeconomic factors, and other factors such as levels of (dis)ability, age and gender. This means that neither home nor place can be a starting point. Of necessity, the material and what is place-specific are also related to more general political and social processes (Papakostas & Gawell, 2021). Perceptions of, and measures taken for marginalized groups and places, as well as socioeconomic development, set conditions that affect homemaking. However, it should be emphasized that the home and the immediate neighbourhood should be carefully examined, since, for example, a neighbourhood does not by definition constitute a community. Instead, we see homemaking as a way in which people try to gain control over their lives, and this includes negotiating specific understandings of home and place.

In relation to the participants’ shared experiences of everyday practice and their experience of home and the surrounding area, our place attachment as researchers was important in terms of fully understanding central aspects of people’s immediate surroundings and for the feeling of trust and belonging. It was also important in order for the participants to gain trust in us as researchers and to begin the journey from place outsiders to place insiders.

References

- Addams, J. (1912). Twenty years at Hull-House. Macmillan Company.

- Afriyanti, R., Prakoso, S. & Srinaga, F. (2021). Place attachment in the context of displacement and Rusunawa in Jakarta. Earth and Environmental Science, 764(1).

- Alawadi, K. 2017. Place attachment as a motivation for community preservation: The demise of an old, bustling, Dubai community. Urban Studies, 54(13), 2973–2997.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H. (2019). Doing things together: Exploring meanings of different forms of sociality among autistic people in an autistic work space. European Journal of Disability Research, 13(3), 168–78.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Kourti, M., Jackson-Perry, D., Brownlow, C., Fletcher, K, Bendelman, D., & Dell, L. (2019). Doing it differently: Emancipatory autism studies within a neurodiverse academic space, Disability & Society, 34(7–8), 1082–1101.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H, Elmersjö, M., & Kings, L. (Red.). (2021). Aktionsforskning - socialt engagerad forskning i samhällsvetenskapen: möjligheter, utmaningar och variationer [Action research – socially engaged research in the social sciences]. Studentlitteratur.

- Blunt, A., & Sheringham, O. (2018). Home-city geographies: Urban dwelling and mobility. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518786590

- Costa, S., Coles, R., & Boultwood, A. (2014). Walking narratives: Interacting between urban nature and self. I C. Sörensen & K. Liedtke (Ed.), Specifics: Discussing landscape architecture. JOVIS Verlag GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868598803-012

- Cristoforetti, A., Gennai, F. & Rodeschini, G. (2011). Home sweet home: The emotional construction of places. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(3), 225–232.

- Deboulet, A., & Lafaye, C. (2018). La rénovation urbaine, entre délogement et relogement. Les effets sociaux de l’éviction. Annee Sociologique, 68(1), 155–184.

- Donnelly, S., Raghallaigh M. N., & Foreman M. (2019). Reflections on the use of community based participatory research to affect social and political change: Examples from research with refugees and older people in Ireland. European Journal of Social Work, 22(5), 831–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1540406

- Eikeland, O. (2012). Action research: Applied research, intervention research, collaborative research, practitioner research, or praxis research? International Journal of Action Research, 8(1),9–44.

- Elmersjö, M. (2020). Värdeskapande frivilligt socialt arbete. En rapport om verksamheten Unga station Vårbergs förankringsprocess och värdeskapande förmåga [Value-creating voluntary social work. A report on Unga station Vårberg’s anchoring process and value-creating ability] (Research reports 2020:01, Södertörns högskola). Elanders.

- Elmersjö, M. (2021). Att forska tillsammans med praktiker – om lärande, roller och tillgänglighet i forskning [Researching with practitioners - about learning, roles, and accessibility in research]. In H. Rosqvist, M Elmersjö, & L. Kings (Ed.), Aktionsforskning – möjligheter, utmaningar och variationer. Studentlitteratur.

- Elmersjö, M., Hultqvist, S. & Hollertz, K. (2022). Moral stress and moral agency in Swedish eldercare: A study protocol on a participatory action research project. Social Science Protocols, 5(1).

- Estrella, M. L. & Kelley, M. A. (2017). Exploring the meanings of place attachment among civically engaged Puerto Rican youth. Journal of Community Practice, 25(3–4), 408–431.

- Fitzgerald, H. E., Burack, C., Seifer, S. D., & Votruba, J. (2010). Achieving the promise of community-higher education partnerships: Community partners get organized. In H. E. Fitzgerald, C. Burack, & S. D. Seifer (Eds.), Handbook of engaged scholarship: Contemporary landscapes, future directions: Volume 1: Institutional change (pp. 201–221). Michigan State University Press.

- Frid, M. (2021). Collaboration, movement, and change: An intra-active action research approach. Forskning og Forandring, 4(2), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.23865/fof.v4.3303

- Fullilove, M. T. (1996). Psychiatric implications of displacement: Contributions from the psychology of place. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(12), 1516–1523.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Hartley, M., & Harkavy, I. (2010). Engaged scholarship and the Urban university. In H. E. Fitzgerald, C. Burack, & S. D. Seifer (Eds.), Handbook of engaged scholarship: Contemporary landscapes, future directions: Volume 1: Institutional change (pp. 119–129). Michigan State University Press.

- Holmqvist, M. (2015). Djursholm: Sveriges ledarsamhälle. Atlantis.

- Hultqvist, S. (2021). The participatory turn in Swedish ageing research: Productive interactions as learning and societal impact. Educational Gerontology, 47(11), 514–525.

- Hörnqvist, M. & De los Reyes, P. (Eds.). (2016). Bortom kravallerna: Konflikt, tillhörighet och representation i Husby [Beyond the Riots: Conflict, Belonging and representation in Husby]. Stockholmia.

- Kale, A. (2019). Building attachments to places of settlement: A holistic approach to refugee wellbeing in Nelson, Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101315.

- Kemmis, S. (2009). Action research as a practice-based practice. Educational Action Research, 17(3), 463–74.

- Kings, L. (2021). Civilsamhället och marginaliserade områden: Att vara på plats och att göra plats [Civil society and marginalized areas: Being on place and doing place]. In A. Papakostas, & M. Gawell (Eds.), Att göra stad i Stockholms urbana periferi (s. 189–209). Stockholmia förlag.

- Macq, H., Tancoigne, É., & Strasser, B. J. (2020). From deliberation to production: Public participation in science and technology policies of the European commission (1998–2019). Minerva, 58(4), 489–512.

- Manzo, L. C., Kleit, R. G., & Couch, D. (2008). “Moving three times is like having your house on fire once”: The experience of place and impending displacement among public housing residents. Urban Studies, 45(9), 1855–78.

- Masso, A. D., Vidal, T., & Pol, E. (2008). La constructión desplazada de los vínculos persona-lugar: Una revisión teórica [The displaced construction of people-place bonds: A theoretical review]. Anuario de Psicologia, 39(3), 371–85.

- Papakostas, A. & Gawell, M. (Red.). (2021). Att göra stad i Stockholms urbana periferi. [Making a city in Stockholm’s urban periphery] Stockholmia förlag.

- Plunkett, D., Phillips, R., & Ucar Kocaoglu, B. (2018). Place attachment and community development. Journal of Community Practice, 26(4), 471–82.

- Riolo, F. (2020). The social and environmental value of public urban food forests: The case study of the Picasso Food Forest in Parma, Italy. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.10.002

- Rutherford, G. E., Walsh, C. A., & Rook, J. (2011). Teaching and learning processes for social transformation: Engaging a kaleidoscope of learners. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 31(5), 479–92.

- Sørensen, M. C., & Wilms Boysen, M. (2021). Forskerpositionen mellem facilitator og faglig ekspert i aktionsforskning. Forskning og Forandring, 4(2), 86–105. https://doi.org/10.23865/fof.v4.3310

- Spokane, A. R., Mori, Y., & Martinez, F. (2013). Housing arrays following disasters: Social vulnerability considerations in designing transitional communities. Environment and Behavior, 45(7), 887–911.

- Stratford, E. (2009). Belonging as a resource: The case of Ralphs Bay, Tasmania, and the local politics of place. Environment and Planning, 41(4), 796–810.

- Thrift, N. (2008). Re-animating the place of thought: Transformations of spatial and temporal description in the twenty-first century. In A. Amin & J. Roberts (Eds.), Community, economic creativity, and organization (pp. 90–121). Oxford University Press.

- Thurber, A. (2021). The neighborhood story project: S practice model for fostering place attachments, social ties, and collective action. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 49(1), 5–19.

- Valli, C. (2015). A sense of displacement: Long-time residents’ feelings of displacement in gentrifying Bushwick, New York. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1191–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12340

- Westoby, P., Lathouras, A., & Shevellar, L. (2019). Radicalising community development within social work through popular education: A participatory action research project. British Journal of Social Work, 49(8), 2207–25, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz022