Introduction

Education is predicted to be an important part of the digitalisation of society (World Economic Forum, 2016). In a national strategy for the digitalisation of the Swedish school system the Swedish government (2017) envisions Swedish schools at the forefront of using the opportunities of digital technology. The strategy addresses all levels in the school organisation to develop adequate digital competence and expresses the expectations of principals to lead digital development at their local schools to meet these requirements. In addition, the concept of adequate digital competence was added to the Swedish preschool curricula (Skolverket, 2018), which further clarifies principals’ responsibility for leading school development and creating conditions for teachers to implement the new policy in educational practice.

While one criterion for being considered a successful school leader is the ability to interpret political requirements (Moos et al., 2011), this is a complex task that involves adapting and integrating new policies to local schools and their specific contexts in appropriate ways. To be able to lead digitalisation, school leaders need insights at all organisational levels (Håkansson Lindkvist et al., 2019) to regard digitalisation as the complex interplay between pedagogy, technology, children’s explorations, organisation and leadership knowledge (Buskqvist et al., 2023). An oft-expressed challenge in relation to implementation, also endorsed in research, is a lack of time (Håkansson Lindqvist, 2019; Metz et al., 2019; Preston et al., 2015). Literally interpreted, running out of time seems like a drastic conclusion to the problem and implies that the perspective on time, and the complexity of leading educational change, leads to procrastination.

In fact, time is central to school leaders’ work. A big part of their role involves organising time to enable education by coordinating the activities of teachers, children, parents, janitors, counsellors, and kitchen staff. Principals lead different processes, such as school healthcare, parent meetings, and collaborative learning activities for teachers. While arranging for these processes, which also have different timeframes, they are responsible for their students’ learning over time. Researchers, as well as political representatives, from a utilitarian perspective, even imply that school leaders can steer time by developing a future education system that enables all students to achieve their educational goals (Huber & Muijs, 2010; Leithwood et al., 2017; Pont et al., 2008). Thus, the temporal orientation of school leaders’ work is prospective via scientific goal- and result-oriented management (Blossing et al., 2015), as well as leading educational reforms and new policies, such as the digitalisation agenda.

A follow-up on the digitalisation strategy (Skolverket, 2019), however, concluded that one-third of Swedish school leaders felt they did not have sufficient skills to lead digitalisation strategically. This argues for the importance of research on how resources, professional development, and time support school leaders in this work (Håkansson Lindkvist et al., 2019). The expectation that school leaders will lead digi-talisation, expressed in policies and steering documents, implies inherent temporal aspects of contemporary local context and needs, as well as leading educational change towards future goals. Simultaneously, it seems that (perceptions of) lack of time can in itself result in losing time. This common, but unexplored dilemma motivates this study on principals’ professional learning and leading digitalisation in preschool education, on which a temporal gaze may shed some light. The research question underpinning this article is as follows: What happens when principals and a researcher theorise on time to understand how to lead digitalisation in preschool education?

Principals’ leadership

The research is itself framed by time (McLeod, 2017), and even research that does not explicitly focus on time takes place in and over time in contexts shaping research topics, methods, and ideas of knowing. The literature on school leadership has evolved from mapping the characteristics of the individual leader to identifying the different behaviours and approaches of successful leadership (Blossing & Ertesvåg, 2011; Leithwood et al., 1996, 2002), to organisational approaches describing school leadership as interactions of school professionals (Hallinger & Heck, 2010a; Leithwood et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2008). An important factor when leading school development is the principals’ knowledge of the school’s history of improvement (Blossing et al., 2015). Therefore, school leaders’ work is a process that controls time when leading the school towards future improvements by relating them to the school’s past. In contrast to the individualistic view, organisational perspectives (Aas et al., 2021) consider school leadership to be a responsive and contextualised relational process (Hallinger & Heck, 2010a). Even so, research states that principals are vital in school development (Day & Leithwood, 2007; Leithwood et al., 2011; Seashore Louis, 2015) and studies that specifically focus on school development regarding digitalisation are no exception (Andersson & Dexter, 2005; Dawson & Rakes, 2003; Ismail et al., 2021; Schiller, 2003). Indeed, they attach even more importance to having individual knowledge, using digital technology (Afshari et al., 2012; Dawson & Rakes, 2003), and understanding implementation (Hughes & Zachariah, 2001).

Research on digitalisation in the preschool context mainly focuses on children’s use of digital technologies (Kjällander & Frankenberg, 2018; Nilsen, 2018; Palmér, 2015, 2017; Petersen, 2015) and teachers’ attitudes towards and use of digital technologies (Otterborn et al., 2019). Meanwhile, studies regarding how principals lead digitalisation in the context of preschools are scarce.

Leading educational change and teachers’ collaborative learning have come to be considered the most important aspects of a school leader’s work (Aas et al., 2021). This has resulted in various descriptions of leadership as encompassing relational processes in school development, for example, professional learning (Fullan, 2006), distributed leadership (Liljenberg, 2015; Spillane, 2006), and leadership for learning (Hallinger & Heck, 2010b).

In contrast to individual approaches on leadership, this article takes a practice-oriented perspective on leadership as the practice of leading (Wilkinson & Kemmis, 2015), referring to principals’ orchestration of the constructions and set-ups of other practices in the school organisation (Kemmis et al., 2012), such as teaching and studying.

Principals’ professional learning

As perspectives on school leadership have evolved, research interest in school leaders’ own professional learning has increased in recent decades. A great number of studies have concentrated on the aspects of principals’ learning in formal education for new principals. The results include the importance of reflections in relation to specific school contexts (Hargrove, 2008; Jerdborg, 2022), metacognitive skills (Hallinger & Heck, 2010b), the difficulty of transferring educational content to practices (Forssten Seiser & Söderström, 2022; Huber, 2010; Jerdborg, 2022) and equipping new principals with the ability to make changes in their everyday practices (Hallinger & Heck, 2010b). With organisational perspectives on schools and ideas of linking education to practice, coaching has been studied as a method to support principals’ learning and address practical issues and changes in their daily practices (Goff et al., 2014; Huff et al., 2013). Furthermore, group coaching was studied as another strategy to enhance principals’ learning and to describe the impact of group coaching, owing to the various perspectives brought together by school leaders from different cultures and contexts (Aas & Flückiger, 2016; Aas & Vavik, 2015). The collegial benefits of professional learning were also expressed by principals collaborating on pedagogical leadership action research (Forssten Seiser, 2017). Research has also shown that principals often lack the space to collaborate with other principals (Aas & Vavik, 2015).

Within this research field, there are two related but different concepts – professional development and professional learning. This article does not focus on development (or learning) as the individual outcome of participating in formal education programmes or professional development courses. Instead, it takes a practice perspective on learning as enacting practices differently (Kemmis, 2021). From this perspective, professional learning is understood as the practitioners’ transformations of professional practices, the knowledge acquired in that process and how the transformation of the practice happens.

Research on principals’ professional learning (Aas & Blom, 2017) connected to their leading practices, is insufficient. More research is required in this area to meet the increased expectations on principals to lead educational change in relation to societal transformations.

Time, temporality and practice

There are many studies on time and practice. The aim of this section is not to review these fields but to describe how the concept of time has been understood and described from ontological perspectives as an introduction to the theoretical perspective on time used in this study.

Time is a fundamental concept in the history of philosophy. The repertoire of perspectives varies from rationalists, following Newton’s naturalistic perspective on time as an object in itself and a fundamental part of the universe, to Kant’s (1991) understanding of time as a cognitive framework existing in the mind of the rational observer, measuring subjective perceptions of events. Bergson (2002) disagreed with the dualistic perspective on time as objective versus subjective and conceptualised time as two-sided: one side is the objective time, measured quantitatively in years, months, and hours. Regardless of various descriptions of objective time, such as rhythms, linear or cyclic, it always contains succession, both before and after. The controversial part of his work is the other side – the duration of time, perceived, lived, and acted, subjective to the individual. Bergson argued that in real life, humans experience time as a continuous, unmeasurable flow rather than in quantitative measures. Time as duration (dureé) conceptualises how time unfolds differently for each person, depending on the interaction of a person’s experiences of the past and the approach to the future. This deconstructed the primacy of clock time and allowed philosophers to think of time in new ways (Massey, 2015). Heidegger (2008) built on Bergson’s duration when taking a phenomenological approach and relating the concept of time to the question of what it is to be human. In contrast to Bergson, Heidegger rejected the idea of separating the outside objective world from the inside subjective human perception of the world. Stating that being (a human) is only possible in an existing world, he founded the concept of Dasein, of being-in-the-world. In this sense, both Heidegger and Bergson, in different ways, approach time as a significant and fundamental feature of human existence (Massey, 2015). Humans are born into existing cultures shaped by history. The past constitutes human life through the heritage of language, discourses, and tools. Being-in-the-world (Dasein) is, therefore, explained as a process of time (Heidegger, 2008) appearing in the happening of events, consisting of human activities. Informed by traditions of the past and aware of the finitude of life, humans understand the event of the present and act towards the future.

These philosophical perspectives on time have affected research on time and practices. Blue’s (2019) review of research on practices distinguishes between different time approaches, such as practices in time, time in practices and practices as time. Practices in time refer to studies that relate to time as an object, describing how practices consume time and make time and how practices are shaped by measurable time in different ways. For example, Blue referred to Shove et al. (2012) and their study on how everyday practices connect in different temporal rhythms, such as sequences, synchronisation and coexistence. Time in practice relates to research on practitioners’ subjective experiences of time, individually or collectively. It includes research on practitioners’ experiences of time shortages (Southerton et al., 2001) and how experiences of practices matter for the ways practices are performed (Spurling, 2015). While these approaches can be related to objective and subjective perspectives on time, Blue (2019) also suggested considering time as a fundamental feature of practice by referring to Schatzki’s (2010) theorisation of the time-space of human activity. Schatzki brought together Heidegger’s ideas on time as the temporal interplay of reflective and projective dimensions of existence and Bergson’s notion of unfolding duration, subjective to the individual. In this sense, Schatzki acknowledged both objective and subjective time but contributed a practice perspective. Schatzki’s perspective on time as practice is used in this study and is described further in the theoretical framework.

Theoretical framework

Human activities are the core of social life, as these activities connect in different social projects (aims of practices, towards an end) through sets of doings and sayings that form social practices (Schatzki, 2002). In Timespace of Human Activity, Schatzki (2010) conceptualises time as the temporal process of social practice, as time is related to a temporal interplay of experiences from the past and ideas of the future that define how practices are enacted in the present. In Schatzki’s own words, a practice is defined as “a temporally evolving, open-ended set of doings and sayings linked by practical understandings, rules, teleoaffective structure and general understandings” (Schatzki, 2002, p. 87).

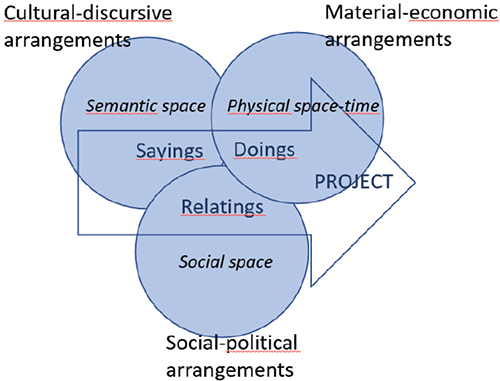

This study uses Schatzki’s (2010) conceptualisation of time to contrast with an objective understanding of time when challenging the prevailing understanding of digitalisation in educational practice. It is combined with the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis, 2014b; Kemmis & Grootenboer, 2008) (see Figure 1), which encompasses practice arrangements of three different kinds – cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements (Kemmis et al., 2008).

Cultural-discursive arrangements appear in the sayings of a practice, mediated in the semantic space, for example, through the language and discourses used in and about a practice. These arrangements enable and constrain what is relevant and appropriate to say (and think) in performing, describing, and interpreting a practice. Material-economic arrangements shape, and are shaped by, the doings of a practice, mediated in the physical space in activity and work. It includes the physical environment, human and non-human entities, schedules, money, and time. Sociopolitical arrangements shape, and are shaped by, relatings, as relations between people and to non-human objects, mediated in the social space as rules, hierarchies, solidarities, and other relationships (Kemmis et al., 2014b). It is only possible to separate the three dimensions analytically to study how practices shape, and are shaped by, one another in ecologies of practices. In reality, sayings, doings, and relatings are always joined as a practice (Kemmis et al., 2012).

The two practice theories share common ontological foundations, as the theory of practice architecture builds on Schatzki’s theory of practices and sites (Kemmis et al., 2014b). According to Schatzki (2002), a practice consists of doings and sayings, with implicit relational connections between the two and the arrangements shaping the practice. Kemmis et al. (2008) share this understanding but add the concept of relating to their theoretical model. Explicating the relational dimension of a practice has analytical implications, as it helps define sociopolitical arrangements and explain how they constitute the practice. In addition to the analytical contribution, the theory of practice architectures is ascribed to inherent transformational potential (Mahon et al., 2017) by addressing the transformation of a practice through changes in understanding, actions, and new ways to relate to conditions of the practice and its environmental context.

Methods and analyses

This article draws on empirical data from critical participatory action research (Kemmis et al., 2014a) conducted with 14 principals leading preschools in a municipality in Sweden. Each participating principal leads, on average, three preschool units and manages 32 employees. They are mostly all experienced and lead preschools in different socio-economic areas of the municipality.

The action research aimed to generate knowledge about how to lead digitalisation in preschool education and about principals’ professional learning. The principals were divided into two groups that met twice per semester at the town hall in the municipality, except for three occasions when the meetings were held on Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The work followed the cyclic process of action research and combined meetings in which participants met to reflect together on the leading practices and individual leading actions carried through in the leading practices to generate practice-oriented knowledge (Kemmis et al., 2014a). The meetings aimed to create collaborative dialogue (Carr & Kemmis, 1986), to construct and reconstruct understandings about leading digitalisation in education, out of experiences of the practices. Participatory action research is a partnership striving for reciprocity (Edwards-Groves et al., 2016) between the participants and the researcher. This was done by creating arenas for communication and recognition of one another’s competencies and contributions (Kemmis et al., 2014a), where the researcher (who is also the author of this text) was an active participant. The theory of practice architecture model (Kemmis et al., 2014a) was presented by the author and used as an analytical tool at the meetings, where the principals identified different arrangements constituting the leading practices. The author participated in the conversation and challenged the understanding of leading digitalisation by asking critical questions and suggesting alternative theoretical ideas about time and digitalisation.

The empirical data analysed in this article consisted of audio recordings from the first year of the action research, comprising eight group conversations, totalling 16 hours of conversations. The meetings were analysed as a communicative practice, with the aim of discussing leading digitalisation in education. Studies using the theory of practice architectures relate to time as a material–economic arrangement, which focuses on time as an object. In order to reconceptualise time from a processual perspective, the author challenged the principals to relate to time as the process of practice, according to Schatzki (2010), whereupon this study examines how time as a cultural–discursive arrangement affected the conversations.

Interpretations and conclusions were made continuously during the process and presented to the principals for peer debriefing and verification (Miles et al., 2014) and to carry out meta-conversations on professional learning. This analytical work was an interactive process following the analytical steps by Miles et al. (2014) – condensation, display and verification, and drawing conclusions. To identify what happened in the communicative practice, the data was categorised based on the analytical concepts of sayings, doings and relatings with a focus on the dimension of time. The categorised data was further compressed and sorted into matrices for data display to get an overview and to discover overall patterns. Finally, conclusions were drawn and expressed as thick descriptions in the findings (Yin, 2013), in the form of a narrative describing how the communicative practice emerged (and the arrangement constituting the changes), which is also illustrated and validated by quotations from the conversations. The quotations were anonymised and coded by letter and number; for example, principal A1 relates to group A, principal number 1.

Findings

The findings describe what happened when principals and a researcher theorised time to understand how to lead digitalisation in education. It visualises how the principals went from conceptualising time as an object to conceptualising time as the process of practice itself. Furthermore, it shows how reconceptualising time changed the understanding of leading digitalisation and the principals’ descriptions of how they enacted leading practices differently.

Time as a material–economic arrangement of leading digitalisation

Time was a recurrent topic in the conversations. When talking about leading digitalisation, the principals perceived time as an asset that could be bestowed. This indicated an understanding of time as a material-economic arrangement in the practice of leading digitalisation. The principals expressed that they felt a lack of time and that they wished they could give the teachers in their organisations more time to explore applications and learn how to operate technical devices:

I believe it is a matter of time if one is about to use digital tools in teaching. They (the teachers) used Stop Motion at my preschool, for example. Then, one needs time to find apps suitable for education and evaluate them. You could absolutely throw yourself out there and try, but you also need to know a bit about “Is this good? Is it functional?”, and I struggle with the fact that I would like to give them [the teachers] … you know, I know these applications and … However, time is a shortage. (Principal 2C)

Even though the aim of the meetings was to discuss leading practices, the dominant part of the conversations focused on the teachers’ use (or lack of use) of digital devices in teaching. The principals described how they struggled to get the teachers to use digi-tal devices when teaching, but they did not know how to succeed in making the teachers change:

I would like to say that the first thing that comes to my mind is the differences among the staff members. Regarding differences in knowledge and interests, but also in their abilities. I have quite many different types of people I need to lead, motivate and inspire. Some do not understand the value or importance of meeting digital development. There are even some who think that children should stay away from that kind of technology to do other things. I also meet employees with burning interests who understand the value of meeting digitalisation but also the challenges that come with it. (Principal 2G)

The above statement indicates that the principals understood digitalisation as a programme to implement in practice and that the teachers hindered them from doing so. As leading digitalisation was described in terms of finding methods to get teachers to use digital devices when teaching, the solutions discussed during the conversations were to organise workshops with digital devices and to give the teachers more time to become familiar with devices and different software.

The principals discussed how the teachers made it difficult for them to lead digitalisation and it seemed difficult for them to take a critical view on their leading actions. The first six months of the action research focused on defining digitalisation in general and digitalisation in preschool education in particular. When doing so, the principals gained a critical approach to leading, as the discussions in the group made the principals realise that it was not their role to define the concept of adequate digital competence (which is central in policies on digitalisation in education) or to concretise it in teaching. The principals expressed that the goal of education was to prepare children for work in the future, but they also said that this is an unclear task, as there will be jobs in the future that do not yet exist. Thus, the principals found it difficult to imagine how digital technology might affect future preschool education, which also made it hard for them to identify the aim of the leading practice, as they did not know what to lead towards:

To speculate on what will become of this, digitalisation and accessibility and information that is so … What will the children need to learn at school? What will it be in the future? Because one does not learn by heart, or like, one does not need to memorise when everything [information] is out there. You can record and … yes, I find it exciting to think about how this will shape humans a hundred years from now. How will people live, and what will they need to … I mean, simply how will they use their brains? (Principal 2D)

Time as a discursive arrangement

In response to the conceptualisation of time as an insufficient asset (material–economic arrangement), the author challenged the principals to reconceptualise time as the process of social practices (Schatzki, 2010). This was to explore digitalisation as part of the historical and ongoing technological development of social practices, in contrast to digitalisation as a programme to be inserted into education. The author concretised this shift by exemplifying it in the preschool setting:

Technological development goes even further back, and digital technology is just a part of it as technology gets more and more refined. There are already … I mean, social patterns and practices have already changed. It is not only something upcoming to prepare children for, but the preschool practices of today are different from preschool practices twenty years ago. I claim that digital technology has contributed to some of these changes. For example, dancing has increased considerably since children are bringing their own cultural content to preschool by streaming music online. (Author)

Reconceptualising time was a way to challenge how the principals related to time and digitalisation in the conversations. Time became a discursive arrangement that enabled the principals to understand digitalisation as an ongoing technological development of society, which in turn made them reflect on how technology had affected different social practices, for example, electronic signatures and the digital transformation of banking and household practices. Reflections on how technological development has changed preschool practices considered different digital platforms for administrative work and systems of documentation. A central topic in the conversations was how digi-tal technology enabled teachers to support multilingual children in their native lang-uages, as the technology made it possible to work with languages that the teachers did not speak. The conversations also addressed changes in the children’s play:

Is it not also about relating to the children’s world? In other words, when using the iPad or the cell phone when checking in the children instead of putting up their pictures on a board. The children’s here-and-now and the world they can relate to at home is very digitalised, I believe. That made me think about when I worked a hundred years ago, and we bought a nice, new, solid stove for the doll play. We thought that they [the children] would cook on it, but the children used it as a microwave, standing in front of it saying ‘ding’, not in line with the adults’ ideas. It was about time. We did not meet the children; we should have bought a microwave, of course. (Principal 2F)

In the quote above, we see a shift in the principal’s perspective regarding time. Earlier, the principals agreed that education should prepare children for work in the future. This quote relates to digitalisation as acknowledging children’s current practices when changing education. When understanding digitalisation as a part of contemporary educational practices, the principals started to describe digitalisation differently:

To me … digitalisation has become a means to achieve the goal. I was stuck thinking of the hardware instead of understanding it as part of the learning process. That it is another dimension to achieve knowledge and that it gives children more opportunities. I find that very exciting. So now I try to learn from the teachers. (Principal 1A)

Reflecting on the past and how technology had changed social practices, the principals started picturing future educational practices, focusing on the possibilities that come with digital technology. They discussed how digitalisation creates accessibility by bringing the world closer together. One example shared was how teachers (together with children) download images of famous buildings from the internet and project them on the walls in a room intended for building and construction to inspire the child-ren. The participating principals talked about how teachers use green screens to create illusions in order to teach about information evaluation. Reflecting on experiences made the principals predict that digital technology might change learning environments even further. They also related to how digitalisation has changed meeting practices, referring to online meetings. Besides possibilities, the principals discussed risks due to changes in communication and imagined scenarios of a society where no one talks to each other but only communicates by texting. On the other hand, they stated that texting as a practice has increased the use of symbols in communication. A change has made communication more accessible to children, not least to children with disabilities, who can find it hard to communicate verbally for different reasons.

The practice-oriented analysis illuminated that different practices in the school organisation complement each other and how practices of teaching and leading are interrelated and complement each other. To grasp the purpose of the leading practice, the principals needed to develop an understanding of digitalisation as a phenomenon and how it had and may affect teaching practice as well as children’s educational practices. When reconceptualising time to think of digitalisation as digital transformation social practices, the principals developed new understandings of teaching and education and reconsidered the aim of the leading practice:

Yes! That’s what I struggle with in my leadership. How do I get them [the teachers] on board and how do I present what you just said? Maybe we should stop talking about digitalisation and technological change. Through time, where are we? And what do we think about the future? Present it differently, not as digitalisation but as technological change. Interesting. (Principal 2C)

The principals went from understanding leading digitalisation as pushing the teacher to use digital devices to creating conditions for the teachers to develop understandings of teaching in a digitalised society and towards the future.

Time as ongoing processes of social practices

Understanding digitalisation as changes in social practices changed how the principals related to the teachers in their descriptions of them. They went from describing the teachers as resistant and incompetent to referring to them as pedagogical experts with the capacity to develop educational practice. This, in turn, changed the ways the principals understood the practice of leading digitalisation:

As I see it, it is about leading the process. I mean, as a principal, I lead the process itself. They [the teachers] are the experts. Everyone is an expert in their own interests, and it is the sum of expertise taking us forward. But I do not regard myself as a spearhead in this [digitalisation], but for me, it is about leading the process. (Principal 1A)

To organise and create conditions for [the teachers]. You have to listen to the natives [relating to children born in a digitalised society] and the spearheads that have come much further because of their curiosity. What do we need, how do we use it, and how do we benefit children? It is about gathering information. It can be different things. We lead together and decide what is beneficial to our children. (Principal 1I)

Understanding leading as creating conditions for other practices was quite contrary to the ways in which the principals initially described their challenges. In the beginning, they described how the teachers hindered them from leading digitalisation due to resistance or incompetence. This changed how the participating principals related to the teachers and the ways in which the principals organised the teachers’ professional learning at the local schools. Instead of struggling to find ways to push teachers to change their teaching, the principals described how they created conditions for teachers’ professional learning about digitalisation in education. This was illustrated in the descriptions of the actions carried through in the leading practices. Some principals described how they arranged for the teachers to meet and collaborate with colleagues to reflect on digitalisation as a process in relation to educational aims. One way to do this was to coordinate teachers in groups to study policy and relate it to practical knowledge. Another strategy described was to bring together teachers with technical skills and pedagogically knowledgeable teachers to plan and lead development evenings for their colleagues. The aim of this was for the teachers to collaborate, discuss and evaluate different methods and generate knowledge about what opportunities different digital technologies bring to teaching practices. Some of the participating principals shared how they organised the digital transformation of educational practices through changes in the pedagogical environment. The strategy was to create environments containing digital devices used in conscious, pedagogical ways. The participating principals articulated that the action research project had a great impact on their professional learning and generated changes in the leading practices. Therefore, the principals all, in some way, organised for the digital transformation of educational practices by combining collaborative reflections with some sort of action for the teachers in their organisations. One of the principals found action research so fruitful that she extended it by developing an action research initiative with the teachers in her organisation.

To sum up, the results illustrate how different conceptualisations of time affect professional learning regarding digitalisation. The perspective on time as a material–economic arrangement contributed to the discourse about lack of time. When time was handled as a discursive arrangement in the conversations, it enabled changes in the principals’ understanding about leading digitalisation, changes in how the principals related to the practices they led and changes in the activities of leading at the local schools. Thus, taking a process perspective on time generated changes in sayings, doings and relatings and changed the practice of leading digitalisation.

Conclusion and discussion

The study shows that when trying to understand and carry through educational change, a perspective on time as an object constrains professional learning, as it reinforces the idea of time as a constraining factor (Håkansson Lindqvist, 2019; Metz et al., 2019; Preston et al., 2015), which contributes to inertia when people fall prey to structures. In contrast, taking a process perspective on time enables a shift in temporality and contributes to agency. Schatzkis’ (2010) theorisation of the time-space of human activity enables us to reflect on social practices (sets of doings and sayings) as processes of time (Heidegger, 2008) and to reconceptualise time as the process of practice (Blue, 2019). In this study, it generated an ontological understanding of digitalisation as the ongoing technological transformation of social practices. In contrast to the self-fulfilling prophecy about lack of time in professional learning and educational change, the process perspective gives agency to time, as reflections of the past and predictions of the future raise awareness when professionals reshape educational practices.

The principals’ approach to educational change shifted from trying to change (digitalise) stable educational practices, to getting hold of and leading ongoing digital transformations in society. Understanding time as an ongoing process of social practices made the principals renegotiate the purpose of their leading and redefine leading as the act of creating conditions for other practices, such as teaching and children’s learning activities. Thus, when taking a critical perspective, the principals discussed policy in relation to educational aims and identified the opportunities and disadvantages of technology in educational practices. This was not primarily to meet political requirements but to acknowledge children’s contemporary use of technologies and improve educational practices in relation to wider educational goals.

In line with the conclusions made by Håkansson Lindkvist et al. (2019), considering school leaders’ need for insights on all organisational levels and the importance of the interplay between them, the results of this study actively demonstrate how different educational practices are intrinsically interrelated and complement one another (Kemmis et al., 2012). In that sense, individualistic approaches to leadership (Blossing & Ertesvåg, 2011; Leithwood et al., 1996, 2002) may delimit principals’ professional learning to encompass the changed knowledge of individuals. Thus, the difficulty of transferring the content to educational practices (Forssten Seiser & Söderström, 2022; Huber, 2010; Jerdborg, 2022), as learning is understood as changes of the individual disconnected from everyday practices. In contrast, a practice perspective on professional learning connects to the principals’ everyday practices and enables actual change, as the sayings, doings and relatings of the leading practice simultaneously shape and are shaped by the sayings, doings and relatings of the collegial meeting practice, and practices principals are leading. In the action research, the principals collaboratively and critically investigated different arrangements constituting their leading, which resulted in changes in leading, not only due to changes in understanding (sayings) and relations to other educational practices (relatings) but also through actions of leading (doings) in everyday practices, as the principals were coming to practice differently (Kemmis, 2021). In this sense, the practice perspective of professional learning addresses what Hallinger and Heck (2010b) considered a goal of professional learning, namely, to equip the participating principals with the ability to make changes in their everyday practices.

Limitations and contributions of the study

One limitation of the study was that it did not access observations of the principals’ leading practices, which would have validated the participating principals’ descriptions of changed leading actions. Furthermore, not all participants are represented in the quotations in the results, as the quotes were picked out to validate the narrative of how the practice emerged rather than to represent individuals.

This study contributes theoretical and empirical reflections about time, digitalisation and professional learning and addresses the need for critical perspectives in practices of educational change. Furthermore, it contributes to a broadened understanding of how action research can be designed and the potential to bring research and practice together to address the needs of the actors in education. It adds an example of how theory and practice are merged, both in professional learning activities and in the process of analysis.

Ethical considerations

The study underwent local routines at Karlstad University for ethical examination (HS 2021/39). Informed consent, which followed the Swedish Research Council’s guidelines (Swedish Research Council, 2017), was signed by the participants. The names of the participants were coded to ensure confidentiality. Furthermore, a document of the participants’ collective expectations of the collaborative work was written.

Ethical considerations were made during the process, striving for reciprocity between the principals and the researcher; for example, continuously reflecting on the authors’ own contributions during and between the meetings, and continuously bringing back the analyses of the meetings to the principals.

References

- Aas, M., & Blom, T. (2017). Benchlearning as professional development of school leaders in Norway and Sweden. Professional Development in Education, 44(1), 62–75.

- Aas, M., Andersen, F. C., Foshaug Vennebo, K., & Dehlin, E. (2021). Forskning på den nasjonale skolelederutdanningen. [Research on the national school leader education]. https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/finn-forskning/rapporter/kunnskapsoversikt-om-skoleledelse-og-skolelederprogram/

- Aas, M., & Flückiger, B. (2016). The role of a group coach in the professional learning of school leaders. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 9(1), 38–52.

- Aas, M., & Vavik, M. (2015). Group coaching: A new way of constructing leadership identity? School Leadership & Management, 35(3), 251–265.

- Afshari, M., Bakar, K. A., Luan, W. S., & Siraj, S. (2012). Factors affecting the transformational leadership role of principals in implementing ICT in schools. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 11(4).

- Andersson, R., & Dexter, S. (2005). School technology leadership: An empirical investigation of prevalence and effect. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41(1), 49–82.

- Bergson, H. (2002). Time and free will: An essay on the immediate data of consciousness. Routledge.

- Blossing, U., & Ertesvåg, S. (2011). An individual learning belief and its impact on schools’ improvement work – an individual versus a social learning perspective. Education Inquiry, 2(1), 153–171.

- Blossing, U., Nyen, T., Söderström, Å., & Tønder, A. (2015). Local drivers for improvement capacity. Six types of school organisations. Springer.

- Blue, S. (2019). Institutional rhythms: Combining practice theory and rhythmanalysis to conceptualise processes of institutionalisation. Time & Society, 28(3), 922–950.

- Buskqvist, U., Johansson, E., & Hermansson, C. (2023) Inbetween literacy desirings and following commands: Rethinking digitalization in Swedish early childhood education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 9(2), 210–220, https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2023.2229021

- Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Knowing through action research. Falmer Press.

- Dawson, K., & Rakes, G. (2003). The influence of principals’ technology training on the integration of technology into schools. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 35, 29–49.

- Day, C., & Leithwood, K. (2007). Successful principal leadership in times of change: An international perspective. Springer.

- Edwards-Groves, C., Olin, A., & Karlberg-Granlund, K. (2016). Partnership and recognition in action research: Understanding the practices and practice architectures for participation and change. Educational Action Research, 24(3), 321–333. https://doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1129983

- Forssten Seiser, A., & Söderström, Å. (2022). The impact of the Swedish national principal training programme on school leaders’ actions: Four case studies. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 7(4), 826–859. https://doi.org/10.30828/real.1120909

- Forssten Seiser, A. (2017). Stärkt pedagogiskt ledarskap: Rektorer granskar sin egen praktik [Strong pedagogical leadership: Principals investigate their own practice]. [Doctoral thesis, Karlstad University]. DiVa. http://kau.divaportal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1145701&dswid=5263

- Fullan, M. (2006). Leading professional learning. School Administrator, 63(10), 10–14.

- Goff, P., Edward Guthrie, J., Goldring, E., & Bickman, L. (2014). Changing principals’ leadership through feedback and coaching. Journal of Educational Administration, 52(5), 682–704.

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010a). Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. School Leadership and Management, 30(2), 95–110.

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010b). Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference in school improvement? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(6), 654–678.

- Hargrove, R. (2008). Masterful coaching. John Wiley & Sons.

- Heidegger, M. (2008). Being and time. Harper Perennial.

- Huber, S. G. (2010). New approaches in preparing school leaders. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (Vol. 4). Elsevier.

- Huber, S. G., & Muijs, D. (2010). School leadership effectiveness: The growing insight in the importance of school leadership for the quality and development of schools and their pupils. In S. Huber (Ed.), School leadership – International perspectives. Studies in educational leadership (vol. 10). Springer.

- Huff, J., Preston, C., & Goldring, E. (2013). Implementation of a coaching program for school principals: Evaluating coaches’ strategies and the results. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(4), 504–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213485467

- Hughes, M., & Zachariah, S. (2001). An investigation into the relationship between effective administrative leadership styles and the use of technology. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning, 5(5).

- Håkansson Lindqvist, M. (2019). School leaders’ practices for innovative use of digital technologies in schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1226–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12782

- Håkansson Lindqvist, M., & Pettersson, F. (2019). Digitalization and school leadership: On the complexity of leading for digitalization in school. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(3), 218–230.

- Ismail, S. N., Omar, M. N., & Raman, A. (2021). The authority of principals’ technology leadership in empowering teachers’ self-efficacy towards ICT use. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(3).

- Jerdborg, S. (2022). Learning principalship: Becoming a principal in a Swedish context [Doctoral thesis, University of Gothenburg]. GUPEA. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/70566/Avhandling_E_version.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Kant, I. (1991). Critique of pure reason. Vasilis Politis. (Original work published 1781)

- Kemmis, S. (2021). A practice theory perspective on learning: Beyond a ‘standard’ view. Studies in Continuing Education, 43(3), 280–295.

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon. R. (2014a). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Springer.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014b). Changing practices, changing education. Springer.

- Kemmis, S., Edwards-Groves, C., Wilkinson, J., & Hardy, I. (2012). Ecologies of practices. In P. Hager, A. Lee, & A. Reich (Eds.), Practice, learning and change. Professional and practice-based learning (Vol. 8). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4774-6_3

- Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating praxis in practice: Practice architectures and the cultural, social and material conditions for practice. In S. Kemmis & T. J. Smith (Eds.), Enabling praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 37–62). Sense.

- Kjällander, S., & Frankenberg, S. J. (2018). How to design a digital individual learning RCT-study in the context of the Swedish preschool: Experiences from a pilot-study. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 41(4), 433–446.

- Leithwood, K., Tomlinson, D., & Genge, M. (1996). Transformational school leadership. In K. Leithwood, J. Chapman, D. Corson, P. Hallinger, & A. Hart (Eds.), International handbook of educational leadership and administration (vol. 1). Springer.

- Leithwood, K., Hallinger, P., & Furman, G. C. (2002). Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration. Springer.

- Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & Pollock, K. (2017). How school leaders contribute to student success: The four paths framework (Vol. 23). Springer.

- Leithwood, K., & Levin, B. (2008). Understanding and assessing the impact of leadership development. In J. Lumby, G. Crow, & P. Pashiardis (Eds.), International handbook on the preparation and development of school leaders (pp. 280–300). Routledge.

- Leithwood, K., & Seashore Louis, K. (2011). Linking leadership to student learning: Empirical insights. Jossey-Bass.

- Liljenberg, M. (2015). Distributed leadership in local school organisations: Working for school improvement? [Doctoral thesis, University of Gothenburg]. GUPEA. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/39407

- Mahon, K., Kemmis, S., Francisco, S., & Lloyd, A. (2017). Introduction: Practice theory and the theory of practice architectures. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Exploring education and professional practice. Springer.

- Massey, H. (2015). The origin of time: Heidegger and Bergson. State University of New York Press.

- McLeod, J. (2017). Marking time, making methods: Temporality and untimely dilemmas in the sociology of youth and educational change. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(1), 13–25.

- Metz, S., Piro, J. S., Nitowski, H., & Cosentino, P. (2019). Transformational leadership: Perceptions of building-level leaders. Journal of School Leadership, 29(5), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684619858843

- Miles, B. M., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Moos, L., Johansson, O., & Day, C. (2011). New insights: How successful school leadership is sustained. In L. Moos, O. Johansson, & C. Day (Eds.), How school principals sustain success over time: International perspectives (pp. 223–230). Springer.

- Nilsen, M. (2018). Barns och lärares aktiviteter med datorplattor och appar i förskolan [Children's learning activities using tablets and apps in preschool] [Doctoral thesis, University of Gothenburg]. GUPEA. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/57483

- Otterborn, A., Schönborn, K. J., & Hultén, M. (2020). Investigating preschool educators’ implementation of computer programming in their teaching practice. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48, 253–262.

- Palmér, H. (2015). Using tablet computers in preschool: How does the design of applications influence participation, interaction and dialogues? International Journal of Early Years Education, 23(4), 365–381.

- Palmér, H. (2017). Programming in preschool—with a focus on learning mathematics. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 8(1), 75–87.

- Petersen, P. (2015). Appar och agency: Barns interaktion med pekplattor i förskolan [Apps and agency: Children’s interaction with tablets in preschool] [Doctoral dissertation]. Uppsala University.

- Pont, B., Moorman, H., & Nusche, D. (2008). Improving school leadership (Vol. 1). OECD.

- Preston, J. P., Moffatt, L., Wiebe, S., McAuley, A., Campbell, B., & Gabriel, M. (2015). The use of technology in Prince Edward Island (Canada) high schools: Perceptions of school leaders. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(6), 989–1005. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214535747

- Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2010). The timespace of human activity: On performance, society, and history as indeterminate teleological events. Lexington Books.

- Schiller, J. (2003). Working with ICT: Perceptions of Australian principals. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(2), 171–185.

- Seashore Louis, K. (2015). Linking leadership to learning: State, district and local effects. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3.

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. Sage.

- Skolverket [The Swedish National Agency for Education]. (2019). Digital kompetens i förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning. Skolverkets uppföljning av den nationella digitaliseringsstrategin för skolväsendet 2018 [Digital competence in preschool, school and adult education]. Skolverket.

- Skolverket [The Swedish National Agency for Education]. (2018). Läroplan för förskolan, Lpfö 18 [Curriculum for preschool]. Skolverket.

- Southerton, D., Shove, E., & Warde, A. (2001) Harried and hurried: Time shortage and the co-ordination of everyday life. University of Manchester.

- Spillane, J. (2006). Distributed leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

- Spurling, N. (2015). Differential experiences of time in academic work: How qualities of time are made in practice. Time and Society, 24, 367–389.

- Swedish Government. (2017). National digitalization strategy for schools. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/72ff9b9845854d6c8689017999228e53/nationell-digitaliseringsstrategi-for-skolvasendet.pdf

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice. Swedish Research Council.

- Wilkinson, J., & Kemmis, S. (2015). Practice theory: Viewing leadership as leading. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(4), 342–358. https://doi:10.1080/00131857.2014.976928

- World Economic Forum. (2016). New vision for education: Fostering social and emotional learning through technology. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_New_Vision_for_Education.pdf

- Yin, R. K. (2013). Kvalitativ forskning från start till mål [Qualitative research from start to finish]. Studentlitteratur.